Thoughts on a serial killer

As Peter Sutcliffe terrorised the women and girls across the nation, the police and media showed us how little they care

Jacqueline Hill, the last known victim of Peter Sutcliffe

Yorkshire had a bad winter in 1980. The weather was continually wet and cold, and women everywhere were seen almost running once the light fell, grabbing their coat collars tight against their necks for protection. They were seen walking in the middle of the roads to give them enough space either side to run away, and to avoid the shadows. Yorkshire in 1980 was Ripper territory.

I’d moved to Leeds from the North East the year before. Soon, I joined Women against Violence against Women (WAVAW), a radical feminist group set up to campaign against the shocking levels of sexual brutality by men towards women. I met, purely by accident in a bookshop, the feminists who were waging a battle with West Yorkshire police over the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper, a serial killer who had by that point already murdered 10 women and left five others for dead. Four had been killed in Leeds.

I became hooked on the cause. We would parade around the city centre painting, “No Curfew on Women, Curfew on Men!” on billboards. We organised “Reclaim the Night” marches attended by hundreds of women disgusted at the way their lives had been curtailed by one man. Some spoke about the violence they lived with from partners. Others said they had always lived under a curfew of a sort, because men who enjoyed hurting women and children were often on the streets at night looking for prey. A woman turned up with horrific burns on her face and neck; her husband had thrown acid in her face as punishment when she left him.

In November 1980 I was walking back to my room at the YWCA in Headingley after a late night out with a girlfriend. She had gone ahead of me to buy chips before the shop closed. I was 18, and it was the first time I had lived independently. Our hostel was at the top of an unlit hill. Apart from the pub halfway up, the area was deserted. I started to walk quickly up the hill, keen to get back to the warmth of our tiny room. It was freezing cold.

I was thinking about the Ripper. Nine days earlier, he had attacked Theresa Sykes, a 16-year-old girl out for Bonfire Night in Huddersfield. She had just bought cigarettes from the corner shop and was walking on a path near her house. Sutcliffe had appeared as if from nowhere, run after her, and struck her on the head from behind. She tried to grab the weapon as she fell, and later told police it was metal. She described the man as about 5’6”, with black hair, a beard and a moustache.

Theresa Sykes

Theresa’s screams were heard by neighbours and by her boyfriend. Sutcliffe ran off, with Theresa’s boyfriend in pursuit, and hid under a hedge in a nearby front garden. It was the closest he ever came to being caught, until he was.

I had read about the attack in salacious detail in the press, and was feeling scared when I suddenly noticed a figure jogging up the hill. As he came closer I could make out his shoes. Actually more boot than shoe, but quite small feet for a man. A dark shadow around the face suggested a beard. He was not tall, maybe 5’6”. I didn’t run, but waited, weirdly fascinated. Was he coming for me? Was he the Ripper? I walked backwards, looking to see if he changed direction. He stopped, partly under a light coming from the pub 100 metres away. He was dark, with curly, almost frizzy hair and a full beard. His skin was pale. He looked fairly ordinary.

I decided he wasn’t the Ripper. He was just a nuisance, a man out to frighten me for amusement. I headed to the pub and he followed. For a few seconds I was actually teasing him, daring him to follow. He did. He was so close I saw his breath in the cold air, perhaps three metres away. He was wearing a brown suede jacket. And then I saw something that terrified me. His hands. They were ungloved and held outstretched in front of him, as if he were beckoning a small child or dog to come to be patted. He had wide jacket pockets. I ran; he followed.

When I got to the pub, he was gone. I hadn’t seen how close he got to me, but I know he was close to catching me. Was it the Ripper? I decided not, because he could have got me if he’d wanted to. I felt stupid, as though I had offended this man who was just going about his business, not feeling the cold in his hands. Perhaps he was just lost.

The next day friends persuaded me to report the incident to the police. Millgarth Police Station in the centre of Leeds, opposite the sprawling bus station, is not an inviting building. I asked the desk officer in charge of the Ripper enquiry. He laughed and said, “Why love, has he followed you in here?” I said no, but that he might have been following me the night before in Headingley. “Been on a night out had you, darling?” he sniggered. I asked if I could do a photofit description of the man. The officer told me I’d been watching too much TV. I went to a phone box over the road and called my WAVAW friends. Two came to the station and said we would have a sit in until they provided a trained officer to do the photofit. One was shouting that the police “cared fuck all about catching the Ripper, because he is only killing women.” I was embarrassed and scared. The trained officer arrived after four hours. My photofit was, it turned out, almost identical to the one provided by Marilyn Moore, left for dead by the Ripper in Leeds in 1977.

The so-called ‘Ripper Squad’

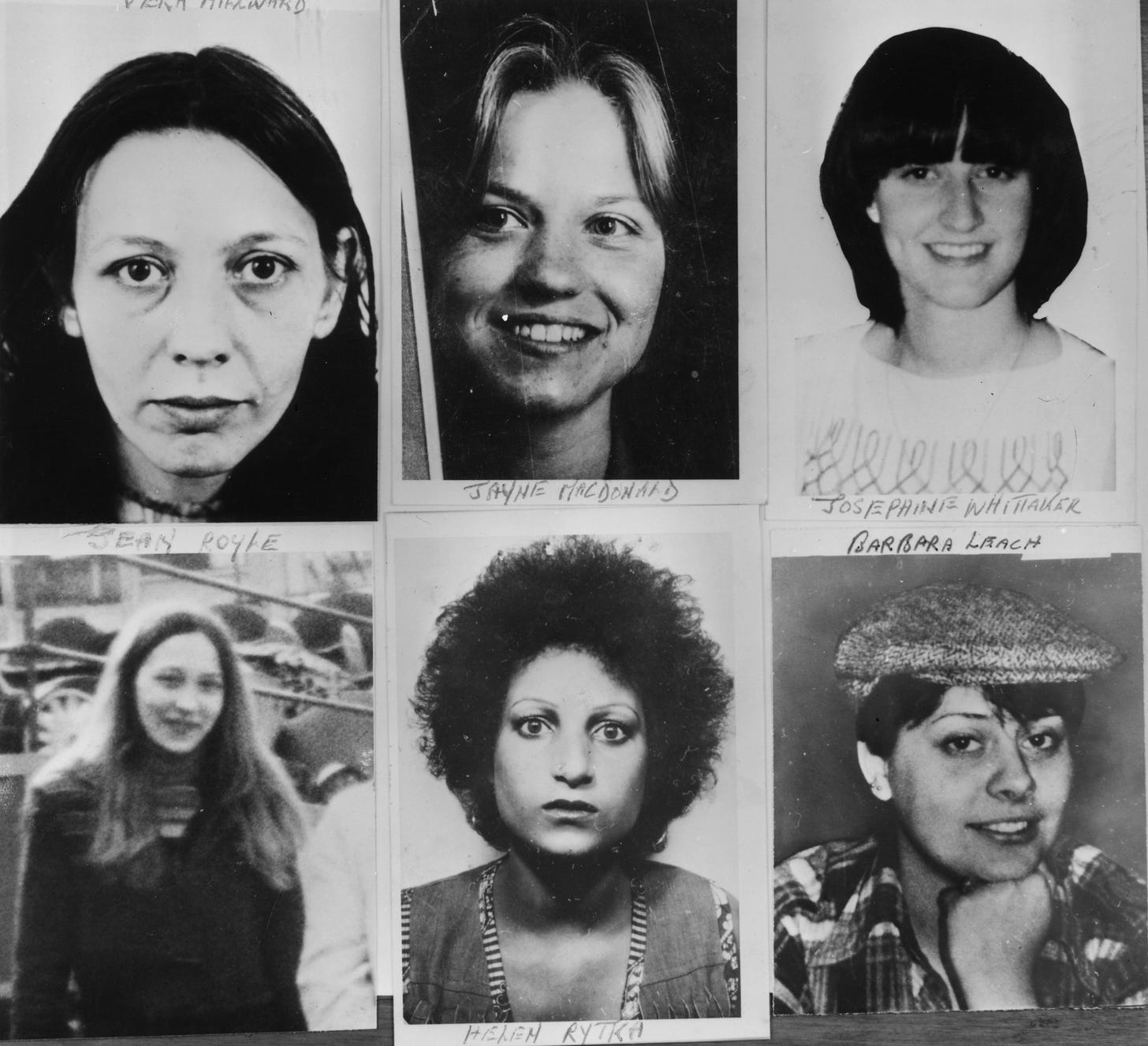

Since 1975, when the first victim Wilma McCann was discovered, West Yorkshire Police had been criticised for dragging its feet. The Yorkshire Ripper (named after Jack the Ripper, a killer of prostitutes in Victorian London) just kept killing – with hammers, screwdrivers and knives – and the police investigation was no further forward by the time the body of his fifth victim, Jayne MacDonald, was discovered in June 1977.

The newspapers declared that this was the Ripper’s “first mistake.” Jayne was 16 and a bank cashier. The Ripper’s previous victims were considered by most people to be worthless scum, because they were all, to various degrees, involved in prostitution. People would say, “Well, it’s an occupational hazard,” and, “At least he’s not targeting innocent women.” The prostitutes Sutcliffe was maiming and killing were disposable. They asked for it. He was doing a public service in ridding the streets of them. So the police, though concerned, were not frantic. After all, the general public certainly wasn’t pressurising them to catch him in the way it had when children were going missing from Manchester and being buried on Saddleworth Moor.

Jayne’s body was discovered close to her home, which was six doors away from Wilma McCann’s. Like the other women the Ripper had killed, Jayne’s head had been caved in with what appeared to be a hammer and she had been stabbed several times.

Police said they knew who the Ripper was. They called him “Wearside Jack.” A man had sent a letter to police and a national newspaper in March 1978 claiming to be the Ripper. He later sent a tape recording of his voice and experts said he was from the North East. The tapes were played and handwriting displayed on billboards from the time police received them right up until Sutcliffe was caught. I would be in Leeds market when suddenly we would hear over the radio, “I’m Jack. You are no closer to catching me now than when I first started.”

Of course, Wearside Jack wasn’t the Ripper, but a hoaxer. In January 1981 the world would discover the Ripper was Bradford lorry driver Peter Sutcliffe, a married man who was liked by colleagues and neighbours. An ordinary man. But police refused to accept the truth about Wearside Jack until they caught Sutcliffe. And while they were obsessed by a Wearsider, a Yorkshireman killed six more women.

Assistant Chief Constable George Oldfield, the police officer in charge of the Ripper enquiry, took the taunts contained within the letters and tapes as a personal challenge. The man on the tape was openly goading him, questioning his abilities as a police officer. Oldfield responded by holding a televised press conference while apparently drunk, telling the hoaxer, “This is between me and you. You may think you will win, but you won’t. There may be a few more pawns before I beat you, but I will!” The women of Yorkshire were the pawns. That press conference prompted some of us to storm the Yorkshire Evening Post to protest about the handling of the enquiry and to demand that the editorial the following day asked why the police did not care about the victims. We got nowhere.

I never met Jacqueline Hill, a 20-year-old student in her final year at Leeds University who became the Ripper’s final victim. But we probably occupied the same physical space at some point. After she was murdered, l learned that she did her shopping at the Arndale Centre, between my hostel room and her halls of residence. But our lives were miles apart in other ways. I was a working-class feminist activist, a lesbian, and a bit of an anarchist. Jacqueline, from a respectable middle-class household, was preparing to enter the career world. I was shoplifting to supplement my unemployment benefit. Jacqueline never knew me, but she was soon to become a landmark in my life, and someone with whom I would form an unbreakable link.

On the evening of November 17, 1980, she was on her way home, yards from where I had seen the bearded man three days earlier. The Ripper had driven to Headingley at about 9pm looking for a woman to kill. He parked his car opposite the Arndale Centre and decided to pass the time eating Kentucky Fried Chicken. Spotting a young woman walking past on her own, he switched on the ignition and turned up Alma Road, overtaking her. He stopped his Rover, and waited for Jacqueline to walk past. After she did, he got out of the car and followed her for a short distance before delivering a blow to her head as she was passing an opening. He said afterwards, “She made some noise.” A little later, a woman began walking down the road and Sutcliffe quickly pulled Jacqueline into a standing position before dragging her approximately 30 yards onto some wasteland behind the Arndale. There he pulled her clothes off and stabbed her with a screwdriver repeatedly in the chest and once in the eye. “I thought she were staring at me,” he would later tell police, during the 26 hours he spent making his confession after his arrest. He also said that “Miss Hill” had “turned round and looked as if she was adjusting her skirt or her stocking, and this suggested that it was the behaviour of a prostitute. God invested me with the means of killing.”

At 10 the next morning on some wasteland behind the Arndale Centre, I was on a demonstration against “video nasties,” low-budget films that encourage and legitimise sexual violence towards women. I had a placard saying “Men off the Streets.”

Five years after the Ripper’s first murder, the only solution the police had come up with to protect women was to impose a curfew on them. With the Yorkshire Evening Post used as mouthpiece, women were urged to “stay indoors” and told, “Do not go out at night unless absolutely necessary, and only if accompanied by a man you know.” (Sutcliffe gave the same advice to his sister.) In response, WAVAW mocked up police notices and flyposted them all over the city. “Attention all men in West Yorkshire,” the notice read, “there is a serial killer on the loose in the area. Out of consideration for the safety of women, please ensure you are indoors by 8pm each evening, so that women can go about their business without the fear you may provoke by simply walking behind her.” For one glorious night, the streets were deserted.

At the video nasty demonstration, a youth whispered to me, “I wouldn’t have you, love, not even if I were the Ripper.” Another shouted, “I hope the Ripper gets you.”

I walked back towards the hostel after the demo, through Headingley and on to Cardigan Road. Something had happened near the Arndale Centre. There was yellow tape everywhere, and at least 15 police cars. Police on foot were keeping onlookers away. I knew. I asked a policeman, “What’s going on?” “It’s the Ripper, love. Off you go. Off you go home.” Jacqueline’s body had been found earlier that morning. With Jacqueline’s murder, the threat of the Ripper was finally noticed by Britain’s middle-class. No longer was he “just” killing poor, urban prostitutes in poor, urban areas; “innocent” women started thinking that they were now in danger, something prostitutes had known for five years.

After news of Jacqueline’s murder was released on November 18, police stations were inundated with information from the public. They got 8,000 letters, mostly anonymous. Women named their husbands and sons as suspects. One letter was from Trevor Birdsall. In it he named Peter Sutcliffe, and gave information on an assault he had witnessed on Olive Smelt in 1975. Birdsall and Sutcliffe were out drinking together one night, he wrote, when Sutcliffe insisted they drive through the red-light district. There, Sutcliffe leaped out of the car having seen Olive, and came back bragging that he’d “done her.” (He’d hit her on the head with a rock in his sock.)

Birdsall had been suspicious of Sutcliffe for some time before he went to the police, but he didn’t think his friend was capable of killing. Anyway, the police were looking for a Geordie, so it couldn’t be Sutcliffe, who spoke with a Yorkshire accent. When nothing happened after Birdsall’s initial report, he repeated his allegations two weeks later at Bradford police headquarters. Still nothing happened.

On Friday January 2, 1981, Sutcliffe prepared to kill another woman, and decided to go a little further afield. It was freezing weather in Sheffield, but 24-year-old Olivia Reivers still left her two toddlers at home and went out to make some money from punters in Sheffield’s street prostitution area. Her friend Denise had refused to get into the car with the man with the beard and dark frizzy hair because, she said, he had “funny eyes.” But Olivia did – she needed the £10. As the man was about to coerce her out of the car to kill her, two patrolling police officers checked his number plates and discovered they were stolen. They knew Olivia was a prostitute, and that all instances of men found in suspicious circumstances with prostitutes now had to be referred to the Ripper squad. Sutcliffe was arrested, and asked to be allowed to urinate. The next day, hearing that Sutcliffe was still in custody, one of the arresting officers decided to go back to where Sutcliffe had been picked up to have a look around, because his behaviour had been “strange.” He found the ball-peen hammer and knife that Sutcliffe had dropped behind the water tank where he’d urinated.

On the second day of questioning, Sutcliffe said, “Well, it’s me, I’m the Ripper. I’m glad it’s all over.” The next day he appeared at Dewsbury Magistrates Court. He was hurried into court with a blanket covering his head while a crowd of over 2,000 screamed, “Die!” “Evil!” and, “Hang the bastard!”

That day I was in Leeds organising a conference on sexual violence. We mourned Jacqueline Hill and all the other women. I was supposed to be his 13th victim. She would have been alive if he had caught up with me. I was glad to be alive, but felt I owed a debt. I promised Jacqueline I would never be complacent about sexual violence towards women. On my way home that night I armed myself with a spray can and daubed, “Sutcliffe – male not mad,” on the walls along the route.

Sutcliffe taught me a valuable lesson. He could carry out his murderous attacks for so long because he was an ordinary man. He was a regular bloke, and drew no special attention to himself. He enjoyed drinking, using prostitutes and violence. These were all normal activities in his world. This is why Birdsall thought no more of it when his friend hit Olive Smelt over the head with a stone in his sock, simply because she was a prostitute. Other men – significant numbers if we are look at the numbers of murders and assaults of prostitutes by punters and passers-by – also attack prostitutes for no apparent reason. Such behaviour is not seen as unusual.

The police made many mistakes, but a fundamental one was assuming the Ripper was killing because he hated prostitutes. Like other murderers who seek their prey in red light areas, Sutcliffe knew that killing a prostitute is relatively risk free, compared to women who matter to someone. “The women I killed were filth,” he told police. “Bastard prostitutes who were littering the streets. I was just cleaning up the place a bit.” Sutcliffe wasn’t the only one to feel this way. Even Michael Havers, the prosecutor at Sutcliffe’s trial, said, “Some were prostitutes, but perhaps the saddest part of the case is that some were not.”

Sutcliffe claimed voices from God had urged him to kill prostitutes. But a comment he made in his police statement was more revealing. Sutcliffe said of Helen Rytka, his eighth victim, “I had the urge to kill any woman. The urge inside me to kill girls was now practically uncontrollable.” It wasn’t a divine mission, but misogyny. Prostitutes were just the easiest to get to. Perhaps they were also partly the reason, according to the 1983 Sampson report into the Ripper investigation that looked into why finding him took so long. The turning point in the investigation should have been after the attack on Marilyn Moore in December 1977. Sutcliffe had already killed seven times. Marilyn provided a photofit of her attacker, which bore a stunning resemblance to Peter Sutcliffe, as well as a description of his car. “If her photofit had been compared with those by other survivors,” the report said, “the similarity is so striking that it is beyond belief they would not all have been linked and considerable emphasis given to tracing the bearded man. One name that would certainly have emerged was that of Sutcliffe as he had already been seen and his description provided in November 1977. If Sutcliffe had been re-interviewed at any point soon after December 1977, the officers would have seen his striking resemblance.” The police was blamed for its inefficient filing system, for its misplaced focus on Wearside Jack. But perhaps, as long as the Ripper was killing prostitutes, the police didn’t care enough.

In May 1981, Peter Sutcliffe was convicted of the murders of 13 women and the attempted murders of seven more. Many, including police officers, believe he attacked and killed other women whose bodies haven’t been found. He was ordered to serve life in prison, and has been told he would never be released. In 1984, he was diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic and moved to Broadmoor secure hospital, where, in 1997, a fellow patient stabbed him in both eyes with a pen and left him blind in one. Sutcliffe died in November 2020.

By Mo Lee, who survived an attempted murder by Sutcliffe

After his arrest, police searched Sutcliffe’s truck. There they found a scrap of paper on which was written this epitaph. “In this truck is a man whose latent genius if unleashed would rock the nation, whose dynamic energy would overpower those around him. Better let him sleep?”

Thank you Julie for all your work to protect women and girls from male violence. This was a sobering read.

I wonder what makes some men hate women so much - and what can be done about it? Is it hate or is it just a desire to feel power over someone at any cost?

What we really need are feminist trained police forces, forces of women and men trained in the realities of systemic male sexual lust and resentful rage for and against females and the historical mistakes made by the largely all-male (10% female) police forces in the 80s as a result of likely a big chunk of these male police being misogynists too. They were certainly snobs not valuing the lives of young prostitutes or working class girls. It's frightening to think you were so close to this monster, Julie. And so young. This misogynistic male violence must not be allowed to continue. All boys and men especially need to be better educated in the basics of cultural misogyny (woman-hate) and to realise JUST HOW MANY men (and too many women) are misogynistic, with a high percentage of those males being violently misogynistic. The actual numbers need to be much more widely known. Feminists are accused of being 'man-hating' (as I am accused by my long-estranged sons), but history abundantly shows that it is men who have actively and horrendously hated on women and paid few consequences for their violent and non-violent hate, including their burning of hundreds of thousands of accused 'witches' in Europe and the US, usually the more wealthy and clever older women, so mothers and grandmothers mostly, as well as lesbians of course, whose money the church took, as it took nuns' dowries and lives. By contrast, there is no physical evidence of women hating on men, if you can't tell my sons that. I did try but clearly failed to raise my sons to be feminist allies, but failed. I wrote a PhD on battered women who kill and the NZ justice system's failed treatment of such cases. The subject matter made all the men in my life, except the boys' father, nervous and angry. My brother took it as a personal insult, though he is not a wife-beater. I can't hate men too much when I have been married to a man for 37 years and birthed and raised two sons who I still very much love. It is their love that is in question. Arguably, women do not hate men enough. We marry our abusers and murderers all too often, that's for sure. But for those 13+ murdered women, and for ALL the other women murdered by violent misogynist cowards like Sutcliffe, we need to learn that lesson and show it by our actions in the police, parliament and beyond that we DO finally care enough about our mothers and sisters and daughters enough to fight for their right not to be beaten, stalked and violently killed on the streets - or in the home.