[This essay is adapted from the book Plain Radical: Living, Loving, and Learning to Leave the Planet Gracefully, about the political/intellectual life of my late friend Jim Koplin. Jim was my role model for how to engage feminism as a man. For more information on him, go to https://robertwjensen.org/category/jim-koplin/.]

Jim Kopklin

Jim Koplin was born on the farm, in a house without electricity that was heated by a wood stove, during a raging January blizzard. His father had taken the wagon to get the doctor when his mother went into labor in the evening, but Jim was born before Emil could return. It was a harsh entry into a world both terrifying and beautiful.

Jim loved the central Minnesota land on which he grew up—he was full of stories about working on the farm, tramping around in the woods, summer swimming in the nearby lakes—but what went on inside that house was not the source of happy memories. The circumstances of his birth—alone with his mother, in the cold—changed little throughout his childhood. The joyful stories flowed freely, but Jim spoke very little about details of that harshness. Apart from a handful of old pictures, he kept very few records from his childhood and virtually nothing regarding his father, Emil. But after Jim’s death, as friends gathered and went through his belongings, we found in his files one yellowed letter about his father.

On June 9, 1933, John L. Townley, Jr., sat down in his law office in Fergus Falls, Minnesota, and composed a short note to Mr. Emil Koplin of Vergas. Writing in his official capacity as the Otter Tail County Attorney, Mr. Townley wrote to put Emil on notice. The letter, in its entirety, reads:

Your sister, Mrs. L.M. Gullickson, now living in Vergas, has complained to me as County Attorney with reference to your conduct towards her at the Rose Lake Pavilion and also on the road between Vergas and Frazee. Even though Mrs. Gullickson is your sister you have no right to assault or to unduly abuse her. Mrs. Gullickson has explained quite fully the circumstances and it appears that your conduct has not been that of a gentleman.

There are no details in Jim’s files as to the nature of these assaults. In rural Minnesota in 1933, I am not sure what would have constituted undue abuse by a man against his adult sister in public, but those few sentences speak volumes not only about Emil but also about the world around him. It appears that Mr. Townley believed Mrs. Gullickson’s account, yet these two attacks in public led not to an investigation and possible criminal charges but instead a polite rebuke by a gentleman, with a reminder of the need for more gentlemanly conduct.

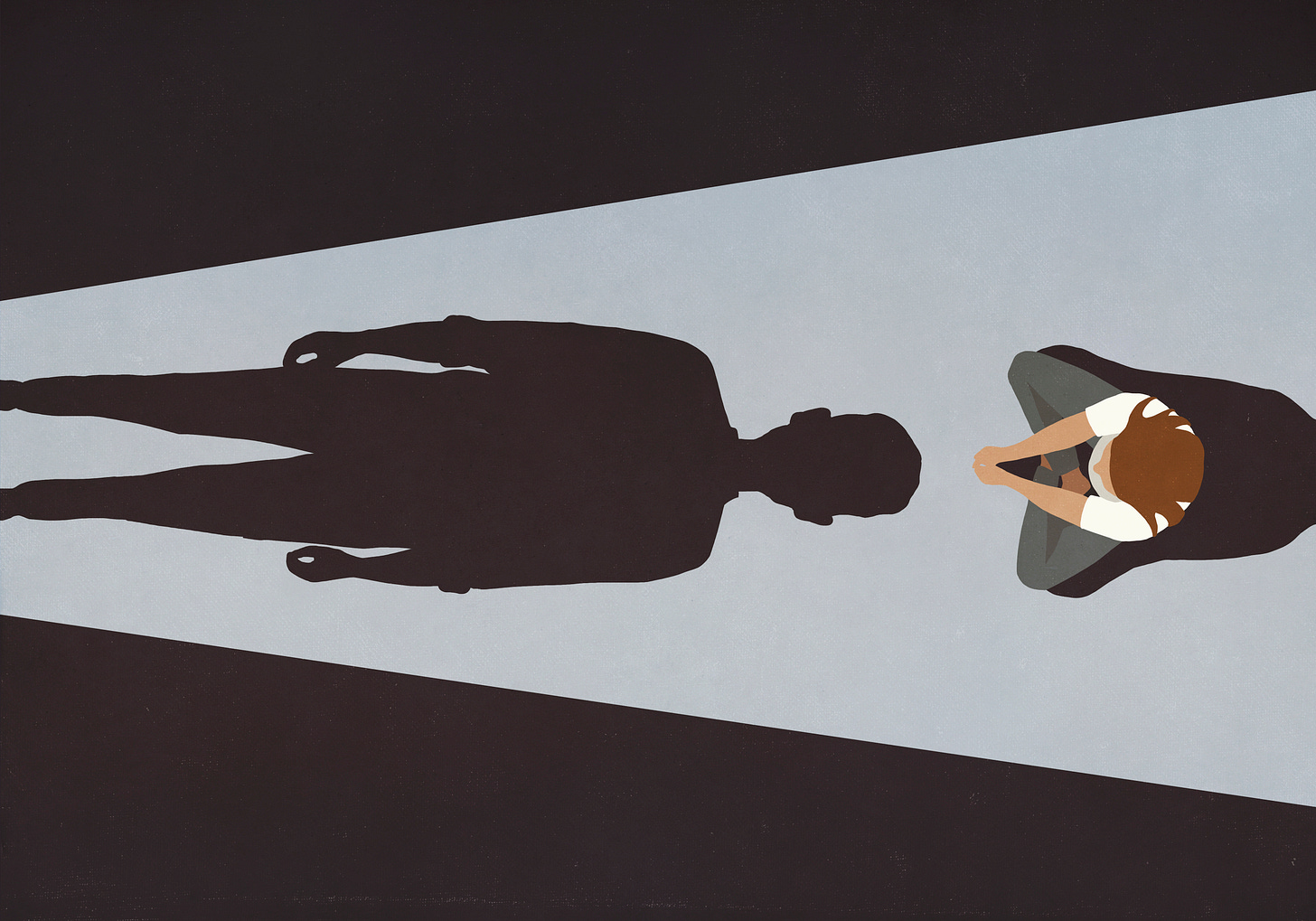

Jim was four months old when his father received that letter. Jim was born into a house ruled by a man who did not hesitate to assault his own sister in public, severely enough that it drove the sister to contact a public official, no doubt a major step at that time, when such problems typically were dealt with quietly within the family. The attorney’s warning suggested that as a brother, Emil had some right to control his sister, but that right did not include undue abuse. Emil Koplin was a mean and violent drunk, living in a culture in which mean, violent drunks were tolerated so long as they controlled their violence, out of public view, confined to the home.

Jim had never spoken to me about that incident and had never mentioned the attorney’s letter or why he kept it. He was blunt in describing his father but never detailed specific acts of violence that he or his mother endured. He simply said that his mother was a victim of what we now call domestic violence, and he once speculated to me that he likely was conceived as a result of what we now call marital rape. From what little Jim said, I gathered that Emil had broken the spirit of Dorathea early in the marriage. Though he offered no details of his own experience, Jim also made it clear that his mother was not the only target of his father’s violence, and on occasion he would make a remark that hinted at that reality. When talking about how trauma is manifested in the body, Jim told me that starting when he was about five years old, he threw up at night three or four times a week, every week, regularly. This was apparently ignored by his parents until it stopped at about age ten, and the explanation offered was that the “outgrew” whatever the problem was.

“My father treated his animals better than his wife and child,” Jim once told me. “Let’s leave it at that.” From Jim’s account, his father was a hard-working farmer who took seriously his obligation to care for land and animals. It seems that his father’s main, and perhaps only, virtue was his work ethic and that on all other fronts, Emil was a failed person, generally unlikeable, feared more than respected in town. Jim told me that when he left for college, he knew that he was leaving his mother to face that terror alone, and that he knew she wouldn’t last long by herself. He also knew that if he stayed, there would be two broken people, two lost souls.

While Jim never wavered on his assessment of his father—there were no moments of “but he was my dad and I loved him”— he took no pleasure in his rejection of Emil and didn’t enjoy talking about it. When the subject of his estrangement from his father after his mother’s death came up, he offered few details and made it clear he had made a choice not to revisit that part of his life. He had dealt with it, decided to walk away, and had no interest in looping back to re-examine. Jim took great care in making decisions, examining a question from every angle, but once a decision was made, he stayed on course. On this question, he said he had no regrets. This is how he described it in a letter to me, at a point when I was struggling with my family’s pathology:

After my mother died, [my father] lived for another 10 years or so. I am not too clear about this, but expect I saw him only once. When we got back from France in the summer of 1970, I was at Hampshire getting the college ready to open. He had a stroke and was hospitalized. I flew to Minnesota to check on the situation and talk to my stepmother. That was it. She let me know he was battering her in a repeat of my mother’s situation. She was indirectly asking me for help. I told her I had done that trip (in gentler words) and that if she needed help she should turn to her own adult son. [Emil] died after a series of strokes, I believe the next May, the night before Sally and I were to leave for two months in France. I called [my stepmother] and told her to bury him and keep whatever was in the estate—I was leaving for France as planned. All this is now 20 years back in my life—and I rarely revisit the story in any form. (February 5, 1996)

He didn’t revisit, but he remembered. I always had the feeling that Jim had detailed recollections of it all, memories that never faded in intensity, to the very end of his life. It was as if he remembered too much, too clearly, and had to close that door or risk being overwhelmed by it. Given how much time he and I spent talking about and analyzing the violence of the world, especially men’s intimate violence, it was hard not to notice how little he talked about this part of his history. In other realms, including very private matters about sexuality, he was not hesitant to speak of his own experience: “My first source of knowledge, my primary laboratory, is my own body/heart/mind,” he wrote in a draft of an outline for a book on male sexuality that he and I once discussed. “I trust most what I have experienced.”

“Terror” is not too strong a word for those early experiences. The few times Jim spoke of that violence, it was clear he was choosing his words carefully, almost tiptoeing around the memories, as if that terror was still close. In that book outline, he started with dedications, including this:

To my mother Dorathea, who brought me into this world

alone

one January morning

on a farm in rural Minnesota

and whose life

in its concrete pain

taught me what the oppression of women

is all about.

Jim learned from that experience, but he resisted being defined by it. Yet who can escape the effects of such a home? Refusing to be defined by that terror, Jim cordoned off that part of his past. That may have been a good decision and may have been the only choice he had, the only way he could survive. But can a choice to shut off one part of our lives be so easily contained? Or do such choices inevitably mean we lose access to parts of our self—or parts of our potential self—that come along with the terror?

——————

Robert Jensen, an Emeritus Professor in the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin, is the author of It’s Debatable: Talking Authentically about Tricky Topics from Olive Branch Press. His previous book, co-written with Wes Jackson, was An Inconvenient Apocalypse: Environmental Collapse, Climate Crisis, and the Fate of Humanity. To subscribe to his mailing list, go to http://www.thirdcoastactivist.org/jensenupdates-info.html.

Every man should learn to control his own violence and stop taking his anger out on women and children.

Wow! He helped open Hampshire College, from which I would graduate 19 years later. It was an experiment between 4 other colleges - UMASS Amherst, Amherst College, Mt. Holyoke College and Smith College. My parents were mathematicians at Smith and Mt Holyoke. It wasn't until I was 16 years old and was lamenting the terror and uselessness of grades that my mother told me about Hampshire. I hitchhiked to my interview and crossed a pasture, showing up in muddy jeans, long, wild hair, and braces. They practically accepted me on the spot. No one would ever know how my mother's experience mirrored Jim's mother's, except for myself who was doomed to repeat it (for a while.) All that education was great, but somewhat like putting lipstick on a pig. Patriarchy endures (but it is my unerring aim to help it not to.)