Three Doors Down

This five part podcast series tells the astonishing story of Sharon Henderson's thirty year campaign to get justice for her daughter's murder

I made a podcast series with Tortoise Media, working with Joanna Humphreys, the best producer in the business. Here is the story of Sharon Henderson and her battle for justice

*********

Sharon Henderson in May 2023 following David Boyd’s sentencing, Newcastle Crown Court

It’s May, 2022, and Sharon Henderson can’t believe what’s just happened. “The police have come to my door,” she tells me, in the broad Sunderland accent I know so well, having grown up in the north-east of England. “The police have charged him, and this time they better get it right.”

The man Sharon is talking about is David Boyd, who the police have had under arrest since 2018. “I’ve fought all these years for justice for my bairn, and I won’t stop til her murderer is locked up for life.”

And in May this year, after almost 31 years of fighting for justice, I watched as Sharon wept tears of relief in the public gallery of Newcastle Crown Court, as the man that had destroyed her life was finally convicted.

In 1992, Sharon’s seven-year-old daughter Nikki was brutally murdered. She had left her grandfather’s flat and walked the few yards across the veranda and down two flights of stairs towards home, keen to get back and play with her sisters. The killer must have been watching: Nikki was taken to a derelict building, hit twice over the head with a brick, and stabbed 37 times. Her body was found by locals from the search party that had formed as soon as word got out that she was missing.

Nikki Allan

Extraordinarily, it took police 26 years to get around to interviewing Boyd, a convicted child sex offender, as a suspect. He should have been caught at the time, but a series of police failures helped him escape justice.

At the time of the murder, 25-year-old Sharon was a single mother to four girls. “We were a happy family,” she tells me, “It didn’t matter that we were hard up, we had everything we needed, and there was a lot of love in our home.”

Sharon’s life had never been easy. She spent most of her childhood in care, and at 16 became pregnant with her first child, Stacey. Nikki came along two years later. “She was my best friend,” says Stacey, who now works as a boxing coach for kids, using the slogan “Knives down, gloves up”.

After Sharon split up with their father, David Allan, she had Naomi and Zara with a new partner. The family and many of their relatives lived on a rundown housing estate known as The Garths. It was a very lively community, with a central courtyard where children would play out whilst parents kept an eye out from the verandas.

Sharon’s flat was on the ground floor, and two floors up, at number 54 Wear Garth, lived Sharon’s father and stepmother. Three doors down from them, at number 38, lived Caroline Branton and her partner David, who at 25 was 20 years younger than her. He went by the name of ‘Smith’ or ‘Bell’. We now know him as David Boyd.

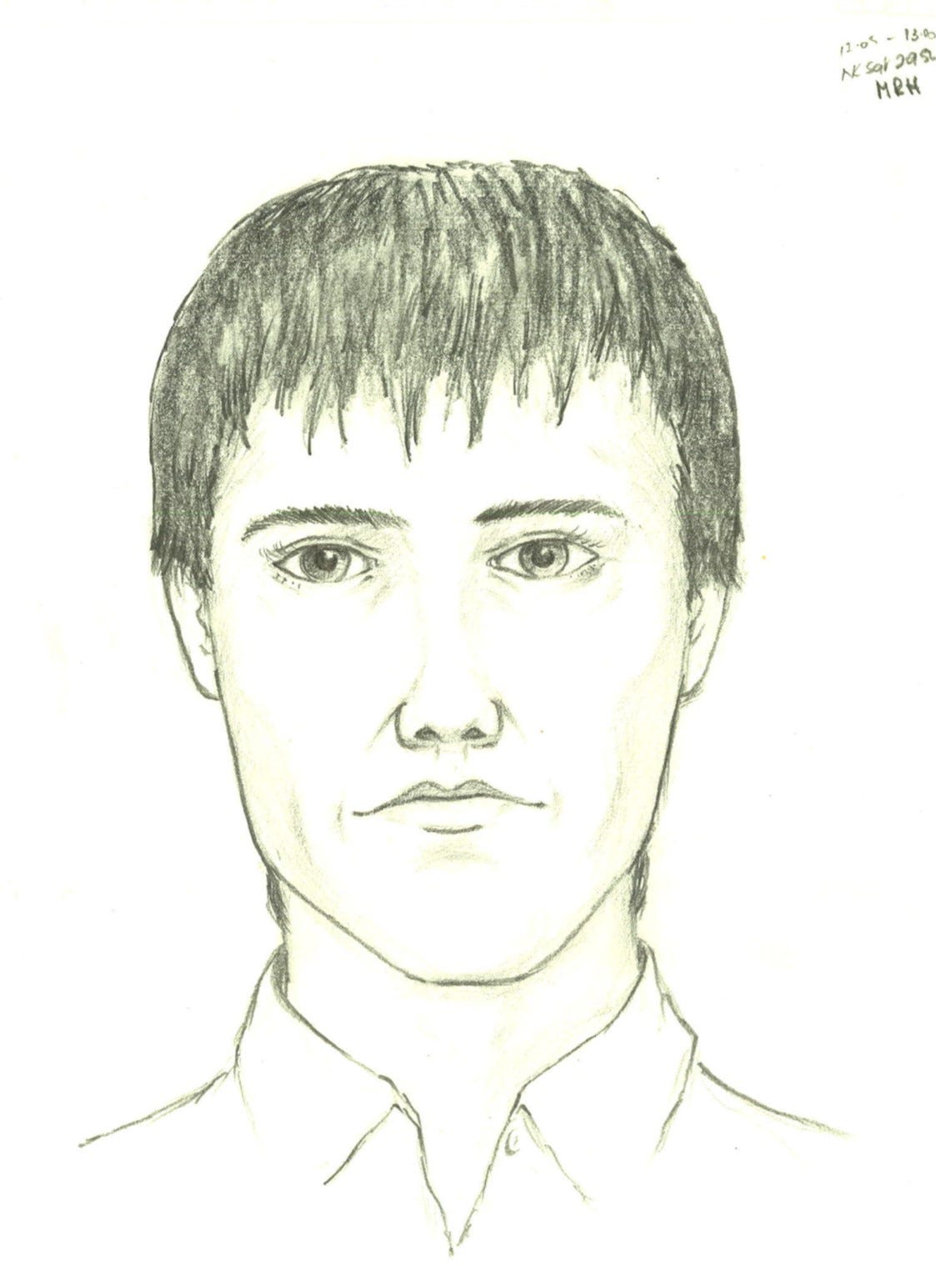

David Boyd, months after he murdered Nikki Allan

Boyd could regularly be found leaning over the veranda, watching the children play. He didn’t work, and was in and out of prison for crimes like theft and burglary. Tall, lean, and with close cropped hair, Boyd was clean-shaven, with a very distinctive large nose and close-set eyes.

Another resident of the Garths was George Heron, a short, skinny man who wore oversized glasses and liked Doctor Who. He stood out as a bit of an oddball. Heron knew Nikki, and would cuddle her and tell her “I love you round the world and back”. Other residents pointed the finger at him from day one, deciding he was the most likely suspect. Police agreed, and picked him up. They spent three days interrogating him, until finally he confessed. However, at the trial the judge dismissed his confession, saying it was inadmissible because police had put words in his mouth. In November 1993, after a trial lasting several weeks, Heron walked free.

“I was in a daze during the trial,” says Sharon, making tea in her sparklingly clean kitchen in a small terraced house in Roker, Sunderland. “I was on loads of medication, and couldn’t face the world, not after what happened to my Nikki.”

The Old Exchange Building, where Nikki’s body was discovered

For 30 years, Sharon was in limbo, desperately trying to find her daughter’s killer, but police said they were not looking for anyone else.

Sharon describes Nikki as a bright and sparky child, a “mummy’s girl” with a beautiful smile. She was deeply loved.

The years since Nikki’s murder have been bleak. Sharon has been sectioned more than once, and arrested many times in a desperate bid to get to speak to police about the case. She dotes on her three girls and her grandchildren, and the family, despite the worst tragedy happening to them, remains close knit.

I first met Sharon in 2006, having seen a story in the local north east news that featured Sharon standing by her daughter’s grave, demanding her body be exhumed. Prior to 2006 the law was that a person could not be retried in a court of law if they had already been acquitted, but this law – known as the “double jeopardy rule” – had been overturned. Sharon wanted to know if, with the advancement of DNA techniques, there was new evidence to retry George Heron for Nikki’s murder.

I began to write about and research the case, and asked my partner, the human rights lawyer Harriet Wistrich, to become Sharon’s legal representative. “I felt I was going round in circles all the time,” says Sharon, “trying to get meetings with the police, writing to the Queen, drawing a map of the estate to see if police had missed anyone out when they investigated it in 1992.”

They had indeed missed someone out: David Boyd had evaded suspicion, despite knowing Nikki (his girlfriend was an occasional babysitter), living three doors down from where she disappeared, and being a convicted child abuser.

Sharon had long suspected Boyd, because he disappeared from the area shortly after Nikki's murder. Whenever she tried to ask Caroline, his former partner, anything about him she clammed up. In 2016, she finally discovered the name he was using [remember, he was using bell or Smith in 1992] and handed the information to the police.

Boyd was brought to justice because Sharon refused to let the case be forgotten. In 2016, Sharon met with the then Northumbria Police Chief Constable, Steve Ashman, who was about to retire. She begged him to reopen the case, and he decided to do exactly that, appointing a crack cold case team the same year. This team did exactly what the original investigating officers should have done and left no stone unturned. But Sharon effectively handed them the name of the man who was eventually convicted.

Through taking DNA samples of over 200 men that were in or near the area where Nikki went missing in 1992, and checking and re checking all of the alibis given during door to door enquiries, police narrowed down potential suspects, finally eliminating all of them but one man: David Boyd.

Artist impression of the man seen with Nikki, minutes before she was murdered

The evidence at trial was stark. Boyd knew Nikki; had lied to police about his whereabouts that night; and DNA found on Nikki's clothing matched his. Extraordinarily, his defence barrister offered no evidence in his favour, and Boyd chose not to take the stand. The judge allowed what's known as' bad character evidence' to be put before the jury which included sex crimes against children.

Boyd had a previous conviction for indecent assault on a nine-year-old girl in 1999 and a conviction for breach of the peace in 1986, after approaching four children, aged eight to 10, grabbing one and asking for a kiss. The jury was not told about two flashing offences he committed in 1986 and 1997. “Who knows how many other victims there are out there,” says Sharon. “I mean, he got away with murder, so he must have carried on abusing kids all the time he was out.”

The trial was hell for Sharon. “Sitting in the same room as Boyd was torture,” she says, tears running down her face, “but I was there for my beautiful daughter. I love her, and I would do anything for her.”

At home, Sharon has created a shrine to Nikki in her outdoor area. There is a little pond surrounded by lights and covered in colourful plants, and in the centre, a plaque with the words “I love you Nikki Allan xxx”.

It is Sharon‘s sanctuary, where she goes to think, and to try to relax. Over these past 17 years I have sat in that space with Sharon on many occasions, talking about police failures and her extraordinary campaign for justice.

Until Boyd was charged, Sharon was tortured by the injustice. The fact that the police had failed so catastrophically made her feel that she and her family just didn’t matter in the way that others do. Today, she is more determined than ever to hold the police to account for their failures since 1992. “Had they done their jobs properly,” Sharon told me during one of our many chats during the month-long trial, “a dangerous paedophile and child murderer would have been locked up 30 years ago,”

Now that the trial is over and David Boyd is safely locked away for life, Sharon can focus on making sure the police answer for their failures. “I don’t want this to happen to any other family,“ she tells me. “I don’t want any other family to go through what we’ve been through.”

“I had to get this sorted out, I have to see this through to the end because I can’t bear my bairns or my grandbairns having to do this after I’ve gone.”

Sharon’s family are proud of her, too. Her daughter Stacey told me, “It wasn’t easy for my mam. It seemed the more time went on, the less the police would listen to her… She turns her grief and her pain into strength. She inspires people, she’s almost superhuman. Our mam never gave up.”

Sharon Henderson

But why did the police go after the wrong man? “They gave up after Heron was acquitted,” says Sharon, angrily, “and all those years since, I felt like I was investigating the case myself, and being treated by police as if I was mad.”

Now that the guilty man is behind bars, what’s next for Sharon? “I want a public enquiry,” she tells me, with steely determination in her dark blue eyes. “Everything has to come out about why the police messed up how they did, and the way I was treated. Being left in limbo when your bairn has been murdered is the worst feeling in the world. There are things I need to sort out yet before Nikki can properly rest in peace.”

Huge respect for Sharon, and her determination to get justice for Nikki in the face of unimaginable pain and relentless obstacles. What an astonishing person. It is to be hoped that what she has achieved will lead to improvements in crime detection that will benefit other victims.

That's a heartbreaking story