The dirty secrets of the global hair trade

My 2017 investigation, as relevant today as it was then. The trade in female human hair is on the rise, with 'hair brokers' sourcing their product from impoverished girls in Ukrainian villages

Whilst there is much to love about Ukraine, women and girls do not fare well there. The mail order bride trade is booming; prostitution is as normalised as it is ubiquitous; and surrogacy is considered a decent way for young women to make a living. It is also increasingly popular with hair traders - the (usually) men who scour villages and impoverished urban areas seeking girls and women who need fast cash.

In am in Ukraine, classed as a developing country by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), to investigate the lucrative trade in human hair, and intrigued as to why this part of the world has become so notorious for it. “Rich, white women such as Victoria Beckham and Britney Spears wear them,” says my driver Artmen, who grew up in Kiev and witnessed girls in his neighbourhood having long hair one day, and shorn hair the next. “You see the advertisements everywhere you go. I suppose it is a good idea when there is nothing left to sell.”

On average, Ukrainian women earn under $150 a month, and are vulnerable to exploitation by capitalists who cash in on desperation. It is no surprise that another booming industry in Ukraine is that of ‘mail order brides.

‘We buy hair for the highest price’, reads the advertisement on a lamppost along a street of run-down apartment buildings on the outskirts of Kiev. ‘The haircut is for free’.

A clinic in Kiev selling the hair of teenaged girls

Hair brokers scour villages, towns and cities searching for long-haired women and girls to target with offers of cash. Over twenty per cent of households in Ukraine are headed by a single mother, and almost sixty per cent live below the poverty line. In other words, it is a perfect place for profiteers to hunt their prey.

Much of the global hair trade, thriving in countries such as China, India, and Peru, relies on accessing its merchandise from communities where long, natural hair is an integral component of feminised beauty, and where the girls and women are poor enough to take the drastic step of selling it, with the added burden of being publicly shamed for doing so.

The hair trade involves the creation of bespoke hair extensions for well-off Western women wanting long, flowing locks. One the brokers have got their hands on the product, the buyers take over, selling the hair to the highest bidder including hair salon owners and trade shows. In London I visited one salon that deals with human hair, and charges clients up to $500 for 20 inch extensions which they pay less than $100 for the product. I was told that the clients were not interested in the original owner of the hair - only that it was untreated and clean. When I explained that I was critical of the industry, and considered it exploitation to farm hair this way, the manager refused to let me name the salon.

Whist researching this topic I came across a magazine article by a journalist who supplements his earnings by selling hair. Vijai Maheshwari, who has built up a successful business selling Ukrainian hair that he markets as ‘Russian’ to mainly US-based customers, explained in his article how the hair business thrives in Ukraine for the simple reason that its women and girls remain impoverished. Parting with long, ‘virgin’ light blonde hair can bring in a month’s wages for the women wishing to part company with their locks.

“When Ukraine’s economy catches up with the rest of Europe,” wrote Maheshwari, “the hair business will move elsewhere.”.

I contacted Maheshwari by email, claiming to be the owner of a hair salon in London, UK. I asked if we could meet when he was next in Kiev and he readily agreed, giving me the address of his rented apartment in the centre of the city.

Maheshwari, well-dressed and brimming with confidence, shows me through to the sprawling apartment, pointing to a shelf near the large window on which several ponytails are on display. I feel uncomfortable seeing this human hair disconnected from the human to which it used to be part of. As I picked up one of the ponytails, feeling it’s silkiness, I wondered about the girl or woman it had come from. “It is virgin hair,” said Maheshwari proudly, “it has never been dyed, permed, or treated with any chemicals, ever.”

Does that mean that it will have belonged to a child, I asked, adding that my customers have ‘a lot of money’, but are socially conscious and would not want to collude with exploitative practices. Maheshwari appeared nonchalant, shrugging slightly and telling me very coolly, “It’s all very consensual.”

I was offered the hair at “a good price” of $2700 a kilo, and a further discount if I took the two-and-a-half kilos in display. Maheshwari sells smaller amounts at $350 for 100 grams but more for the lightest locks. “I charge double for the blondes, so if you only picked out the light ones I would have to charge you more.”

I was told by Maheshwari that there was no need for me to worry about declaring the hairpieces going through customs, and that I should just put it in my suitcase.

Telling Maheshwari I would need time to think, I left, and sensed a slight animosity from him. Perhaps he expected me to hand over the cash there and the. Later that day I emailed him, asking for reassurance that there was no exploitation involved in the trade.

“I do understand your concerns,” he replied, “It’s a commercial transaction between hair gatherers and the girls who want to sell their hair for some monies. It’s usually hair that has been kept in store (it’s a Ukrainian tradition) after a teenage haircut and then handed over. There’s no coercion involved. Usually they have signs all over the small towns and cities of the Ukraine.”

But the women I spoke to who had sold their hair as children or young women have a different story to tell.

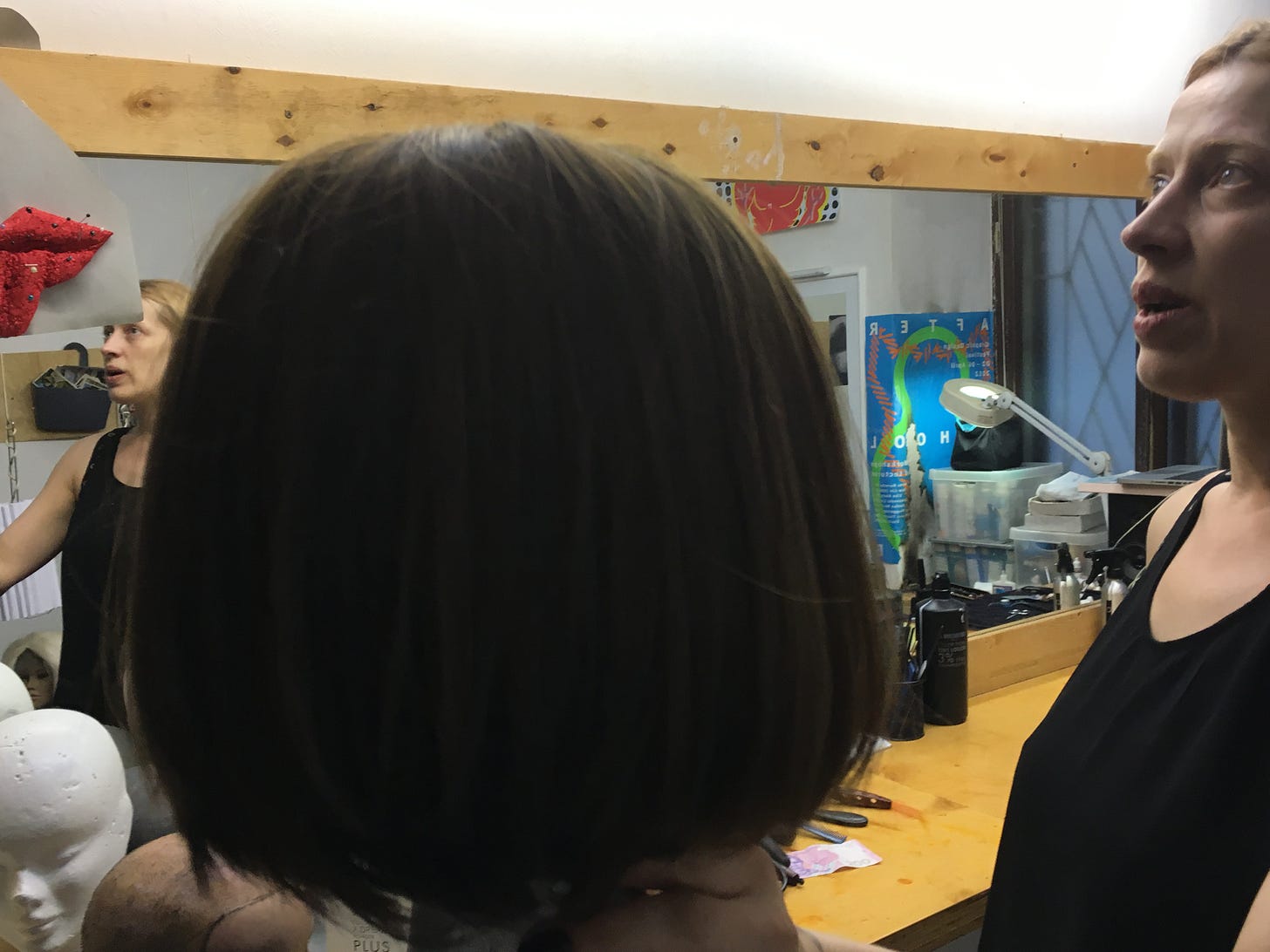

Julia Stets is a freelance wigmaker and hairstylist, working from her apartment in suburban Kiev. Stets buys her hair from China, but in recent years has switched to synthetic hair which she tells me is of high quality and ‘very authentic’ looking. I had asked to interview Stets to ask about her experience in working with human hair, but soon she was recounting a story of her childhood in the rural Western part of the city.

“I faced hair traders in my childhood,” says Stets, “In 1993, when I was 13, the broker gave me $7 for my hair and it was a painful experience.”

“He had promised me $50 but told me my hair was bad quality, and less than he had thought, despite my hair being thick and very long,” says Stets, “There were a lot of girls they tricked like that – it was like a fraud.”

The broker did not ask Stet’s parents for permission before cutting her hair, and treated her “like garbage. He saw I needed money, and just exploited me.”

“This happens in rural China, just the same,” says Stets, who, on discovering this decided to no longer work with human hair. “There are young women who want to find some money to study or get their own life – and here comes the business man, so they sell what they can of themselves.”

I ask Stets if, when she used to buy human hair, she would think about the women it has come from?

“Always,” says Stets, “I imagined the girls, and wonder if they felt like me when it happened, and if they also had money stolen from them by the brokers.”

Alexandra Studio

At the Alexandra Studio in Kiev I meet the proprietor Natali, a young, intense woman who is clearly a very astute entrepreneur. The studio specialises in hair extensions, and Natali has noted that human hair has become an extremely popular product in recent years. The hair is sourced from West Ukraine because it is much cheaper, explains Natali, because the girls are desperate to earn money.

Do her clients ever wonder where the hair comes from?

“No – they don’t bother themselves with that.”

Do the girls ever get upset that they’re losing their hair?

“No, but there was one case when a girl has cut her hair in another salon and came to her and asked her to extend her hair with her own hair because she just changed her mind.”

Is it a human waste product or a body part? We don’t need hair on our head unless for vanity or to keep us warm, but it also has a significant cultural significance. In conservative cultures, women use their hair to establish a group identity. It is deeply connected to the identities of females,

In the Puno region of Peru, a 12-year-old girl with jet black shining hair almost down to her waist stands still, visibly shaking, whilst a man takes the tape measure from around his neck, declares that her ponytail is 22 inches, and tells her that it is worth US$100. the girl says nothing whilst the hair trader hacks off her hair at the nape of the neck, takes a rubber band to fasten around the stump, before carefully placing it in his large hessian bag. “Your hair is filthy,” says the head trader, “and I’m going to have to get it treated. But you can have US$30 for it.”

I connected to Andrea, the now young adult who was the 12 year old girl in Puno, by Skype.

“I now know that their trader was supposed to seek permission from my parents before he could take my hair,” says Andrea. “But he stopped me on my way home from school, and promised that he would only take a bit of my hair, and that we would get have lots of money to go on holiday if he did this. My parents beat me when they thought I had done, and accuse me of spending the rest of the money when in fact he had only given me a fraction of what he had promised.”

As with any industry built on the exploitation of poor, disenfranchised women and girls, organised crime is involved.

In 2013, Police in the Venezuelan city of Maracaibo are hunting a gang of thieves who have been targeting woman for their long hair. The ‘piranha gang’ are hacking women's hair right off their heads, and sometimes they have guns.

As far back as 2006 it was reported[4] that in India, men were forcing their wives and children to sell their hair, and hair brokers were holding children down and shaving off their hair to sell.

In East Jerusalem last year I spoke to a Palestinian woman who told me she had had her hair “stolen” by a gang of young men when she was eight years old, and assumed that her hair had gone to make wigs for orthodox Jewish women, a highly profitable business in parts of the Middle East.

The majority of ‘sheiteln’ that married Haredi women are required to wear to cover their own hair are made in China. Most of the hair used is imported from India, which is much finer than Chinese hair, as well as being far more readily available than the European variety. The cost around £1,500 each, and takes up 150,000 hand tied knots to make.

In India, which boasts a huge hair trade, factory workers as young as 12-years-old spend their days sorting, combing and cleaning the hair collected from villagers, barber shops and the floors of temples. The human hair trade in India is estimated to be worth $395 million per annum, and has in recent years, become a sought-after commodity in Africa.

Human hair extensions are the new Botox, with the key difference being that Botox is an inanimate object. Hair is integral to the identity of those girls and women who live under patriarchal rule, and many are punished and stigmatised if they deviate from the norm of having flowing locks.

As with any business built on the commodification of the human body, supplying human hair from poor women and children to their rich, western counterparts is not ‘meeting a need’ but creating a demand.

On my return to the UK I emailed Maheshwari to tell him that I was an undercover journalist. “Even bad press is good press”, Maheshwari responded, asking me to mention the name of his business in my article.

During our meeting in Kiev, Maheshwari told me that selling hair was a, “commercial and a normal transaction, somebody has hair and they sell it.” I have heard this very same argument used to justify prostitution, womb-rental, and the buying and selling of breast milk. In order to create a marketplace out of a human body it is first necessary to dehumanise it. The hair trade may appear to be fairly benign on the surface, but it exists only because the female body is only afforded worth when it can be turned into profit.

Horrendous! Thank you Julie for another enlightening article. It seems so paradoxical that these western women often encourage their own daughters to donate their hair to children’s cancer charities for wigs.

Thank you Julie. This has sparked our discussion at supper today, and you’ve opened our eyes.