Sexed: My review of Susanna Rustin's book on feminism

Enjoyable, deftly written, and documented by someone who clearly has an investment in this indefatigable movement

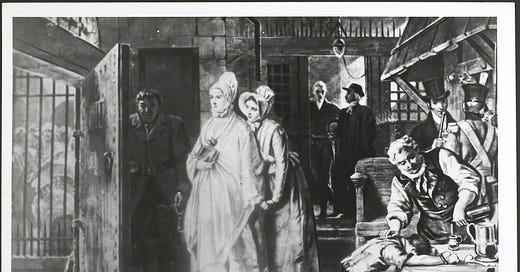

Elizabeth Fry, 1818

In 1823, a woman by the name of Elizabeth Fry succeeded in persuading those in charge of prisons to set up separate facilities for women, so that they were no longer incarcerated with men. Fry had also campaigned for an end to male chaplains and prison officers. By then, she had become Britain’s leading prison reformer,

A philanthropist who enjoyed the privilege of wealth (but also suffered periodical guilt), Fry could have had a very different life to the one she went on to choose – visiting women’s prisons and seeing the atrocious conditions and human suffering. But instead, she prioritised the most abused women, and became one of the most famous women in Britain.

Reading about this remarkable woman in Susanna Rustin’s book Sexed: A history of British Feminism I was minded of JK Rowling, stratospherically famous and stratospherically feminist. Both women feature in the book, Elizabeth fry because of the huge contribution that she made to the rights of female prisoners, which had a significant knock on effect in terms of the way that “fallen women” and in particular poor, abused women were viewed and treated in society, and rolling because of her courageous stance against extreme gender ideology. As Rustin explains in the chapter ‘Feminists: 210 to 2023’, it was the case of Maya Forstater, who had lost her job for stating her belief that biological sex exists, and subsequently lost the case she brought against her employers, that became the final straw for Rowling and prompted her to speak out.

The main focus of Sexed, which begins in the1790s, and, during nine racy chapters, ends up in the present day, is the way that the feminists of today have prioritised the debate on sex and gender identity, bearing in mind that the women's liberation movement is still waiting for its demands to be met. Women are still paid less than men; for many, maternity benefits do not exist…and so on. But bearing in mind that feminists, by which I mean the real ones, the grassroots women that do the work, not those that just claim the word and don't practise what they preach, have always prioritised the campaign to end men's violence towards women and girls. The sex and gender debate sits right in the middle of this universal problem, because if we can't recognise sex, then what do we do about sexism? If we allow gender identity to trump biological sex, what happens to all of those sex based legal, social and political rights that feminists fought for since the 1960s?

Plonkers at London Pride, 2023

Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women, kicks us off, before we embark on a journey that touches upon the foundations of feminist economics before moving to a critique of the male sexologist notion of “female frigidity”. And then, of course, we land on the current, overwhelming battle over sex-based rights.

Rustin, who has admirably spoken out against harmful and misogynistic gender ideology clearly believes there is hope, despite the current anti-feminist climate. In many ways, the UK’s grassroots feminist movement is more vibrant than ever, with conferences and other public events attracting hundreds if not thousands of women from all over the UK and beyond.

But those women, such as Judith Butler (now a ‘they/them’) and Laurie Penny (ditto) putting forward the argument that gender identity should trump sex are not feminists.

Divisions between feminism have long been the lifeblood of the movement, fueling constructive debate and resulting in the development of both action and theory. But one disagreement I have with Rustin is her assertion that new and more insidious divisions regarding sex and gender today dominate the landscape. But those women, such as Judith Butler (now a ‘they/them’) and Laurie Penny (ditto) putting forward the argument that gender identity should trump sex are not feminists. If you dismiss this by tut-tutting about sectarianism and a kind of ‘People’s Republic of Judea’ approach, then tough. Feminism is defined by the campaign to end women’s oppression in relation to men, not as a self-defined individual identity.

Josephine Butler

Butler was a radical of her time, unlike today’s “Sex work is work”, “blow jobs are real jobs” chanting academics and faux feminists.

I was pleased to see Rustin paying proper attention to Josephine Butler (1826-1906), bearing in mind the total distortion of the work of those early feminists that campaigned to end prostitution and ‘the male sex right’ condemned as prudes and religious meddlers. Butler campaigned against the Contagious Diseases Act, passed in 1864, intended to stop the spread of syphilis in the armed forces. Under these laws, any woman in designated military towns could be forcibly inspected for venereal disease. Butler understood that men had to be deterred from sexually exploiting desperate women, and that the victims of prostitution needed help and support, not criminalisation. Butler was a radical of her time, unlike today’s “Sex work is work”, “blow jobs are real jobs” chanting academics and faux feminists.

In the early 200s, the Fawcett Society, as reformist as they were, at least supported Object! in its campaign to reclassify lap dance clubs as ‘sexual entertainment’ venues from ‘gentlemen’s clubs’ in order to object to licensing. Today, they are on the “trans women are women” side, which makes me wonder how they could ever again dirty their hands on campaigns against male sexual entitlement.

Turkeys for Christmas

Sexed is not so much a history of feminism, but more of a collection of voices, past and present, that contributed in some way. Enjoyable, deftly written, and documented by someone who clearly has an investment in this indefatigable movement.

This review originally appeared in the British Journalism Review, December 2024

Looking forward to reading this. I’m always pleased to see recognition of Josephine Butler who I first heard of when my eldest daughter chose her for an A level History project almost 30 years ago, and I helped her track down some archived material about her. These Victorian ladies - privileged gentle folk - faced enormous pressure & criticism. The idea of an ‘age of consent’ came from their campaigning, not as some repressive anti-sex measure but as a means of protecting girls from exploitation.

Grassroots feminism is so important today, just as it always has been. I have fallen out with so many female "feminist friends" in recent times for being all mouth and no trousers! There will always be times to shout and wave our big girl pants in the air, but changing minds and attitudes is the drip, drip efffect we all do every day. My grans, feminists before the word was invented, drummed into to me that you get more change with honey than sharp sticks, and deeds speak louder than words. Hard to do but so worthwhile and great maxims to live by. Keep up the good work, we so appreciate it.