Is paying for sex a crime? Should it be?

“I pay for sex because I can. Because taking a woman out to dinner costs me money, so why not? Because it is my need and she gets to feed her kids.” Sex buyer, Amsterdam.

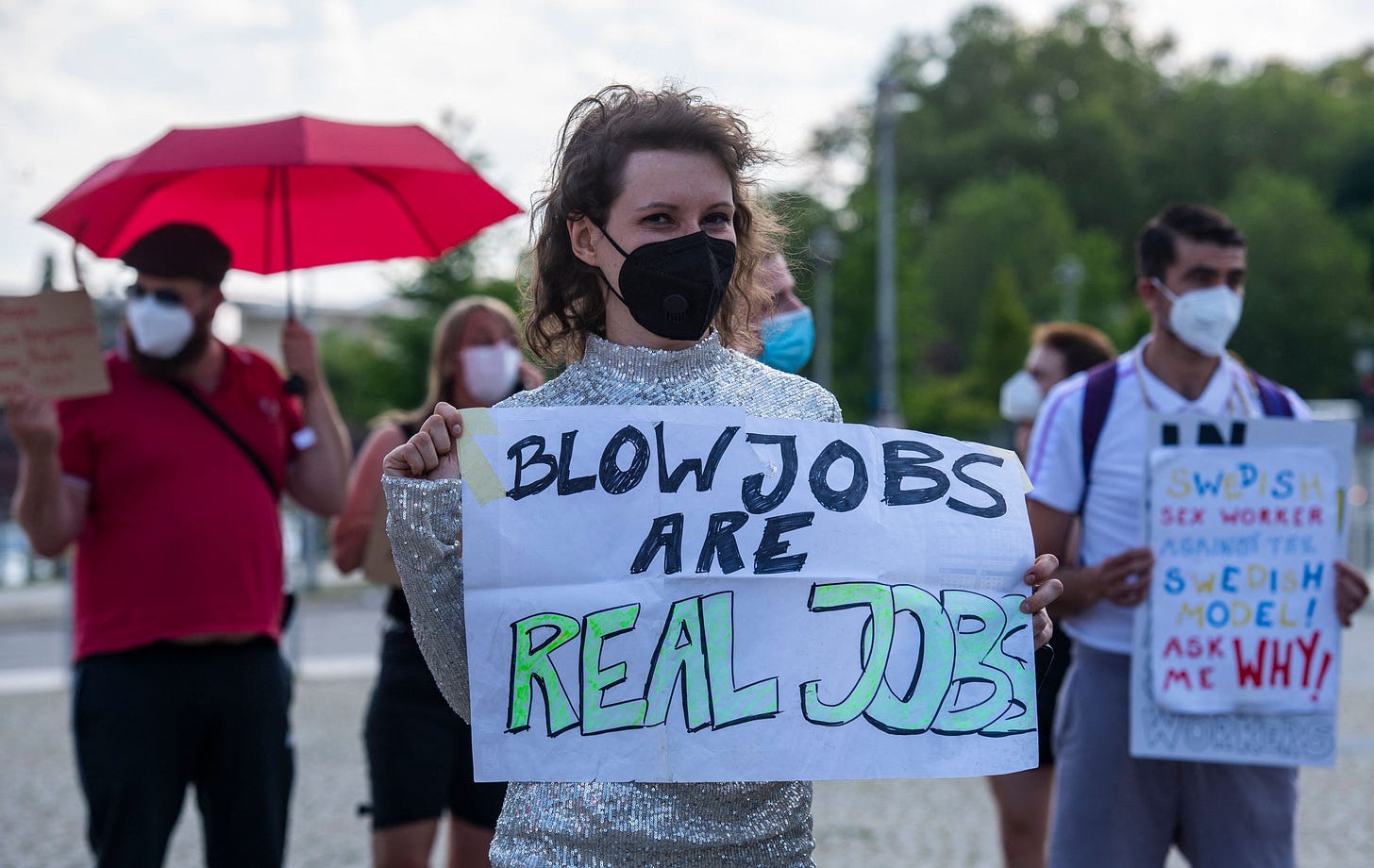

Alba Party MSP Ash Regan has introduced a member’s bill at Holyrood which, if passed, would criminalise those buying sex, while decriminalising those selling it.

Below is an extract from my book, The Pimping of Prostitution: Abolishing the sex work myth (2017) on the men that pay for sex, and how (and by whom) they are defended:

I am heading to a conference on the demand for prostitution at the Dutch Parliament, Den Haag. I share my Easyjet flight from Luton airport to Amsterdam with two groups of young male sex tourists, loudly bragging about how “pissed”, “stoned”, “wasted” and “fucked” they were last time they visited De Wallen, the window brothel area of Amsterdam.

The conference is entitled ‘Men who buy sex: What is their responsibility?’ My friend and colleague Fiona Broadfoot is giving the keynote speech at the event. Broadfoot was pimped into prostitution aged 15, escaped the sex trade 11 years later, and for the past 20 years has been involved in the campaign to eradicate the international sex industry. Most of the delegates are sympathetic to the arguments that sex buyers should be held accountable and that legalisation of pimping and brothel owning has been a disaster. But one woman, sitting at the back of the room, showed her disagreement and displeasure as regularly as she was able to.

The following day Broadfoot and I go to Amsterdam and visit De Wallen. We pass several tour guides and stop by one group, being led by a young hipster who is speaking of the legal sex trade with very little knowledge. The group laugh at the guide’s jokes about how they would “all look at prostitutes together” if they booked his evening walk around the red light district. I ask about trafficking and abuse but he simply trotted out the party line in response.

In the narrow streets in which the window brothels are situated we see two young men approach one of the doors. As one steps inside, the other leans against the wall to smoke a cigarette. We ask if he would be happy to talk to us on the record and to be recorded on my smartphone. He agrees.

Alex started paying for sex when he was 12 years old. “It is so normal here,” he tells us. “In America you have it, in England you have it, but here it is different because it is legal. I come here once a month if I can afford it. I only get charged €20 because I know all the girls and I am a local, but the tourists pay €50. For everything. Most of the women have pimps or lover boys [pimps that pose as boyfriends], but who is going to do anything if they are unhappy? Nobody will.”

He added: “If my sister or mother did this I would be very angry.”

As we are interviewing Alex, Broadfoot spots the woman who had been sitting at the back at the Den Haag conference, standing in the doorway of the Prostitution Information Centre (PIC), who is now taking photographs of us. I recognised her at the conference as Mariska Majoor, who founded the PIC in 1994 and organises commercial tours around de Wallen. Majoor was prostituted from the age of 16 until exiting the sex trade.

Broadfoot asks Majoor why she is taking photos. At that moment, Majoor calls Alex over and tells him we are bad people and that we “have no respect for men who pay for sex”. Then she speaks to Alex in Dutch, and suddenly he becomes very agitated and asks me to delete his interview, which I do. As is usual practice for journalists, I had also been making notes of our conversation in order to remind myself to ask subsequent questions.

At a nearby cafe we see groups of young men who are obviously gearing themselves up for a jaunt around the red light area. I speak to two American tourists who seemed to be unimpressed with the idea of paying for sex but their views, formed mainly from information they had read on a blog about legalised prostitution in the Netherlands, were that this system is safer for the women than any other.

What the survivors say

Rae Story was involved in prostitution for a decade, in the UK, and other countries such as Australia and New Zealand. She exited prostitution in 2015, and runs the Blog, In Permanent Opposition. Story, along with a number of other survivors I interviewed in Germany, Australia, Holland and New Zealand, makes the important point that sex buyers are abusive, disrespectful and often violent whatever legal regime they are paying for sex under:

“You make money for yourself if a guy picks you, but you also spend a lot of the time schlepping about as eye candy for the punters while they get inebriated on expensive plonk. The FKK clubs (upmarket strip clubs with saunas and prostitution services) in Germany are worse because you often have to do it naked. There is no way you can protect against guys pulling your hair, slapping your arse too hard, fucking you too hard, the worst of all: pulling off the condom and ejaculating inside of you... other 'indignities' like dealing with rancid sperm or unwashed backsides etc.”

Holbeck, Leeds, UK. A ‘managed zone’ where, until it was closed in 2021, allowed men to kerb crawl and pimp women with impunity

Aside from women in prostitution, the best evidence of how abusive the act of paying for sex is comes from the men themselves. Over the years I have interviewed a number of men who have accessed commercial sexual exploitation. The first group was in 1999 in the north of England during the Kerb Crawler Re-Education Programme. Over the years, for both journalistic and research purposes, I have spoken to numerous male sex buyers. During the course of researching this book, I spoke to men in legal brothels, illegal off-street establishments and street prostitution zones.

One of the most important research projects I have been involved in was part of a six country study designed and led by Dr Melissa Farley. In 2009, Farley approached me in my capacity as research consultant at Eaves and asked if we would assist with carrying out at least 100 interviews of men who buy sex in London. There was no budget, but we raised just enough money to develop the research tools and buy a mobile phone on which we would make contact with the sex buyers.

We placed an advertisement in one of the free London newspapers that read: “Men! Have you ever paid for sex? An international research team is in London on [date] and would like to talk to you about your experiences and views. Anonymity and discretion guaranteed.” As soon the advertisement went in, the mobile phone we had purchased was ringing off the hook. The only screening we did was to ensure that the men were serious, and had not rung up to get some kind of sexual kick. There were very few that were eliminated. We arranged meetings with 103 of those men throughout the given week.

Four of us were primed to carry out the interviews. We needed to be able to see each other during the interview process to ensure safety. Additionally, the men needed to be reassured that the team would be discreet during the interview process and that their anonymity would be guaranteed.

Having wandered around central London a few times trying to find a venue, I happened upon a brilliant idea. I had been invited to have a drink with a member of the Royal Festival Hall. We would do the interviews in the RFH during the day, before the crowd started to arrive for the evening events, using one of the mezzanine areas, so it would be possible to keep an eye on our interviewees as they were met with the research assistants, outside by the Nelson Mandela statue.

The interviews, which took between 90 and 150 minutes each, went smoothly. That is until interview 99. This man, let’s call him John, turned up early, and the research assistant had not yet arrived at the Mandela statue. John approached the head of security, showed him the ad in the paper and asked where the researchers were who were talking to men about prostitution use.

We were immediately told to leave the venue and that the Royal Festival Hall was a “family facility”, which meant that the nature of our research was unsuitable. After an hour, when there was a change of shift in security, we re-entered the hall and concluded our interviews.

The resulting report was published at the end of 2009 and was launched in British Parliament in early 2010. After its publication I wrote about my experiences of interviewing the men and the main findings in the Guardian newspaper. It is not unusual for those who do research to write about their findings in newspapers, or speak about it on television and radio. It was clearly my own view of the results of the research I have been involved in, and there was plenty of research by pro-prostitution academics that would have reached different conclusions to ours. However, on publication, my editor received a long letter of complaint signed by the usual pro-prostitution academic suspects.

The basis of the complaint was that I was biased, and The Guardian was biased for allowing me to write the piece for their pages. I was promoting my own research, they said, which was biased, so how could the Guardian even pretend to be impartial? Of course, as a researcher, I had followed the ethical guidelines set down by the British Sociological Association. My Guardian article was based on my observations and some verbatim testimony from the men that I obtained with their consent during the interviews. The complainants clearly did not like the fact that the interviewees had pretty much done the abolitionists work for us.

What the men say

As a feminist, I am often of accused making the claim that “all men are potential rapists”. Nothing could be further from the truth: radical feminists do not believe that male babies are born pre-programmed to commit acts of violence against women, nor do we believe that girls are born to be victims. Our view is that under patriarchy, men are given power over women, and that a way of asserting that power is to be violent towards women.

Madrid, 2022, a 20-year-old woman found murdered in a brothel

As one of the London-based sex buyers said to me: “If I wasn’t able to have sex with a prostitute and was frustrated, I might have to go out and attack a real woman.” The ‘real’ woman that this sex buyer was referring to was a woman who wasn’t prostituted. I have heard the same thing said by sex buyers, by women in prostitution, pimps and by members of the public.

Below I have listed a number of the comments from the men in the London study. I have not deliberately picked out the worst, but have simply categorised them to show the range of problematic attitudes developed by the men who commodify sex with women.

Prostituted Women As Products

• “I made a list in my mind. I told myself that I’ll be with different races eg Japanese, Indian, Chinese… Once I have been with them I tick them off the list. It’s like a shopping list.”

• “You get to choose, like a catalogue.”

• “Selecting and purchasing has something to do with domination and control.”

• “It’s like going for a drink, you are not doing anything illegal.”

• “Prostitutes have improved over the years, they’re younger now and better looking and cleaner.”

Prostitution Is about Men’s Uncontrollable Needs

• “I wouldn’t want it abolished, it’s a service I use.”

• “It’s a guaranteed showtime – you’re gonna have a great time with a girl with a great body. You’re gonna enjoy the specific things you like. You’re gonna be able to shoot your load and be totally satiated.”

What they say about the women

• “A prostitute is like an outlet to a pressure cooker.”

• “You pay for the convenience, a bit like going to a public loo.”

• “It is just a job – why would they think otherwise? They don’t feel guilty, in the beginning they have emotions. but it becomes a routine. They die off after a while.”

• “They are girls no one else wants to marry. So they work for sex. No one wants their wife to be a prostitute.”

• “I use ones that I’ve trained.”

Normalisation / pro-legalisation

• “At the end of the day, you’re horny, tired of playing with yourself, so what else can you do?”

• “It’s like having a nice meal.”

• “I’ve been decades without a steady girlfriend – it’s meant I didn’t have to enter a world that didn’t want me. When I think of the gas keys and kiddies’ shoes I’ve bought… I’m not saying I’m a philanthropist but I’ve made a difference.”

• “Maybe if men could get it [prostitution] on the NHS if they are disabled, it would prevent them from raping.”

Deterrence / ambivalence

• On his worst experience of paying for sex: “Very moody girl, language barrier [from South East Asia], she was being forced to do it, mechanical, having sex with her was frustrating. These things give you a feeling of waste of money. That’s when you feel guilty.”

• “They’ve chosen to do what they do to make money – they have to accept what comes with it: the good, the bad, the ugly.”

• On the serial killer in Ipswich: “I kind of felt compassion for the parents of the prostitutes killed. But if you are playing a certain game you should take all that comes with that game. I really feel that way.”

Gross sexism / misogyny

• “It’s just about that moment of pleasure. Liking her was not relevant to the experience.”

• “I get sexual satisfaction for money. She may not get satisfaction, I don’t care.”

• “If she isn’t crying but says ‘no’, I keep on. I only stop if she is really crying.”

• “We call two girls in and have a competition to see who’s better, and ask them to rate each of our sexual performances. After we each do one, we swap, then see who has the highest rating.”

• “They are a necessary evil.”

• “I’m angry at myself for having to go and spend the money, and angry with my wife for making me go.” Punter who says he is a ‘sex addict’ whose wife does not want as much sex as he does.

• “I’ve seen pimps with the prostitutes, yelling. I’ve seen girls dragged back inside apartments. I want the people I deal with to be away from the sordid.”

• “If you go to the wrong one, you might as well be in a morgue, there’s a slab of flesh there.”

Prostitution decreases rape and sexual assault

• “Prostitution should not be abolished, it prevents rape and should be regulated.”

• “If women could give full satisfaction to husbands and boyfriends, then men wouldn’t go to prostitutes.”

All relationships are prostitution

• “There is no need to abolish prostitution. Every woman is a prostitute. Before you sleep with a woman you wine/dine, buy gifts for her before she sleeps with you. So you are spending money on her for sex.”

• “It is actually cheaper to go to prostitutes than a normal woman.”

• “It is simply commercial sex. You go to a woman who is highly sexed, and a normal woman is never as highly sexed as a prostitute. It would be wrong.”

• “The women want to do the job and men want to buy them, so everyone has a role.”

The Ethical John

One commonly heard argument from pro-prostitution activists against criminalising sex buyers is that it will prevent the men who suspect trafficking from reporting it to the police, in case they are arrested. As Cat Stephens of the IUSW said at a meeting in Parliament: “Clients are our best defence against trafficking.”

In her book Not a Choice, Not a Job, Janice Raymond outlines the various ‘ethical John’ campaigns that have been implemented in certain countries. For example: “…the 2006 World Cup Games in Germany provided advocates of ‘ethical sex tourism’ with another version of simply ‘pondering’ the demand”. The National Council of German Women’s Organisations (Frauenrat) set up stalls around the football stadiums and urged male sports fans to “think about” the fact that the women they might have sex with are coerced. Henny Engels, its executive director, made clear they weren’t against men purchasing women for the sex of prostitution: “We have nothing against prostitutes or prostitution. But we are against people trafficking and forced prostitution.”

The idea that sex buyers who see evidence of pimping and trafficking in the off-street sex trade routinely report such matters to the police is risible. Between the 2004 opening of the POPPY Project, the only support and advocacy service for women trafficked into the UK sex trade in London, and prior to a partial law criminalising demand being implemented in England and Wales in 2010, approximately 50 sex buyers contacted the organisation to report possible trafficking cases. All of the men had paid for sex with the women and gone through with it, despite their suspicions. Without exception, the men were hoping to ‘rescue’ the women and move them in to their homes.

Our London research of 103 sex buyers found that 27 percent believed that once he pays the buyer is entitled to engage in any act he chooses with the woman he buys. Forty-seven percent expressed the view that women did not always have certain rights during the prostitution exchange. In addition: “Despite their awareness of coercion and trafficking, only five of these 103 men reported their suspicions to the police. They feared a loss of anonymity, especially fearing their families’ discovery of their use of prostitutes.

Additionally, our research found that 55 percent of the men interviewed said that they were aware that “most of” the women they bought were trafficked, pimped or otherwise coerced. This figure correlates with other research on demand, for example, a study by Anderson and O’Connell Davidson, both fierce opponents of criminalising sex buyers, reports that most men who buy sex are aware of and have witnessed exploitation, coercion and trafficking but this does not affect their decision to buy sex.

Prostitution apologists have been known to dismiss research conducted by abolitionists into sex buyers by claiming it is “biased” and that the researchers have a “hidden agenda”, but it is clear from other research that violence and abuse is often perpetrated by the punters. Even pimps understand this.

During an interview with a Mici, a pimp operating under the legal system in Fethiye, Turkey, I asked about his role and his view on sex buyers: “I think there is a certain attraction/gravitation between the seller and the sold. Some women do not like anal sex or oral sex. They do not like to engage in acts they do not like and sometimes customers force them. They are beaten up, their homes raided by thugs... sometimes two men want to fuck one woman for the price of one. Violence is always there.”

There is even Dutch research on sex buyers that concludes that the men are rarely interested in the wellbeing of the women they buy. Conducted in 2013-2014 by the local municipality of Amsterdam and GGD Amsterdam, a public health service with a focus on HIV/STI prevention and treatment, the survey looked at sex buyers who access prostitution via the legal window brothels. The report, entitled ’In conversation with the Customer’, which focused on the role of the sex buyer in tackling abuse, was presented by one of the researchers at a conference in Den Haag, 2015.

The delegates, largely sympathetic to the introduction of the law to criminalise demand and critics of legalised prostitution, assumed that the research was being conducted in order to highlight how criminalising demand would result in fewer men being willing to report violence and abuse to the police.

A total of 986 sex buyers and 195 prostituted women completed surveys. Interviews were also conducted with 11 sex buyers and 11 of the women. Just over 40 percent of buyers said they would be willing to report abuse. However, based on responses to questions put to the men regarding trafficking and exploitation, and the distinction between “free and forced” prostitution, the researcher admitted that only 13 percent of the overall sample would be able to identify the abuse and spot which women are in danger.

The most frequently mentioned factors that discourage reporting are, according to the Dutch sex buyers: lack of clear and reliable information about abuse; insufficient trust in one’s own judgment; stigmatisation by the government; and distrust regarding how abuse will be dealt with. It is interesting that even under legalisation, such a high percentage of sex buyers claim to be ignorant about how to spot a trafficked women, despite the Dutch government claiming to fund a number of public awareness and education projects on the topic.

The research identified five types of ‘clients’ in relation to the role of the buyer in identifying and reporting abuse. The following, summarised, extract is translated from the Dutch version of the report:

1. The carefree client, who does not feel responsible for abuse..

2. The denier, who feels responsible..

3. Acknowledges that there is a difference between voluntary and forced prostitution. Acknowledges the problem for a small portion of the market with respect to sex slavery and under-aged girls, but does not feel responsible. Denies or trivialises the problem by: blaming the prostitute by stating that a client is not responsible for her choices.

4. The avoider, who sees his role as staying away.

5. The rescuer, who sees his role as‘rescuing’ a prostitute.

5. The whistleblower, who sees his role as notifying the authorities.

The Dutch research came to the following conclusions: “Prostitutes describe the majority of their clientele as ‘good clients’. Nevertheless, most prostitutes have also had experiences with unpleasant clients. In particular, these are clients who make a fuss about using a condom, clients who have used (too much) alcohol and/or drugs, clients who show little respect or who do not stick to agreements.

“Prostitutes have little trust in clients as whistleblowers of abuse. They can’t imagine that clients would actually, sincerely and for the right reasons be interested in the wellbeing of prostitutes.

“In addition, prostitutes describe their clientèle as much less responsible than the clients themselves describe. According to them, clients are primarily occupied with their own pleasure and sexual arousal.”

Clearly, the conclusions would not make those still wedded to the ‘Dutch Model’ of legalising the sex trade very happy.

During the Q&A session, Majoor, founder of PIC, made it clear that she was against any encouragement given to buyers to report abuse: “There is a website on how to recognise signs of abuse,” she said. “I know some [of the women] are sick and tired of clients who don’t want to think whether we are forced [we] just want to earn the money and work and that’s all.”

In response, the researcher asked Majoor if she thought it a “bad idea to have the clients help to find out where the problems are?” She replied: “What I know is that if you criminalise the clients you can totally forget about them reporting [abuse]. The sex workers’ organisations and alliances did a lot of research about the effects of criminalising the clients and this is worse when it comes to safety.”

Sven Axel Mannson, professor of social work at Malmo University, Sweden, was at the event to present his own research on sex buyers. On hearing Majoor’s comments he said: “Personally, having talked to clients over the years I am not so convinced that they will be very much help because they are in their own desires. I have also find that these men are quite manipulative.”

It is no surprise that the approach to punters that was pioneered in Sweden has changed hearts and minds, including of those who were against the idea of criminalising demand prior to and during the early days of its implementation.

Simon Hagström is a police inspector who has been based in the Stockholm police prostitution unit since 2009. I have met Hagström on a number of occasions and found him to genuinely care for the women caught in the sex trade. Hagström, along with the vast majority of his colleagues, took some time after the introduction of the law to criminalise demand came into force in 1999 to fully understand its importance in tackling serious crime.

“What is really important to say is that the Swedish police were strongly opposing this legislation,” says Hagström. “The official standpoint from the police was, ‘We do not want this legislation’. The Swedish police wanted to criminalise the ones selling sex because they thought, along with several political parties, that the law will not be efficient if you only criminalise one party.”

Hagström is pleased to say that he and his colleagues were proved wrong: “There was a lot of attention on this law. I used to think, ‘What is it about this law that is so controversial?’, because this is not a difficult equation. You have traffickers and pimps who want to make money. Who has the money? The sex buyers. If we remove the sex buyers there will be no money for organised crime.

What the Survivors Say

The 50 survivors I interviewed for this book, and the scores of other women in prostitution I have spoken to over the past 20-plus years, all had stories to tell of violence and abuse from punters. Whether they identified themselves as ‘high-class escorts’ or were prostituted from the street, flats or brothels, the women share a core experience: not one had escaped violence while dealing with sex buyers.

I met Nicky in Auckland, New Zealand, in 2016. I asked if the punters were less violent under decriminalisation: “No. Recently I got bottled – I’ve never had that before in my life – a bottle was shoved up me and broken. And the next day I was down the Salvation Army telling them. Then I rang [a friend] and said ‘I’ve been raped’. I’ll start crying – now a police officer will say ‘How big was the bottle, what colour was the bottle?’ It doesn’t matter what colour the bottle was… it was a bottle up me.

“I have been threatened, I have been told to get off the street. I used to always carry a weapon in a long black coat. Then I bought an imitation gun and it looked the part. Then I thought ‘no’ because I’d get done by the pigs whether it’s plastic or not. Then I put a screwdriver down my bra and now it’s just, ‘I don’t give a fuck’.”

Sabrinna Valisce, who was prostituted in Australia and New Zealand both before and after legalisation and decriminalisation, tells me that, contrary to promises from the pro-prostitution lobby, punter violence increased in New Zealand after the 2003 change in the law: “[In 2003] the police violence stopped overnight under decriminalisation, so on that level it was good, but the Johns… within the space of a year the Johns got more violent and had greater expectations. They thought they could do whatever they wanted, thought they had bought your body. I had never had someone say, ‘I paid for your body and I can do what I want’, until decriminalisation,” says Valisce.

Children abused into the sex trade often experience life-changing violence from punters. The men who buy them might find it particularly difficult to delude themselves into thinking that a girl or boy standing on a street corner looking for ‘business’ is making any kind of choice, or that this is something s/he is happy to do. Of all the women I have spoken to who were prostituted as children, only one survivor told me that one time a punter, on realising she was under the age of consent (16 in her country), gave her a reprieve.

Ne’Cole Daniels was 15 and had been turned out onto the streets by a family friend. She tells me about one incidence of violence that had a profound effect on her: “A man pulls up in this nice car, he looks like he has money. So I go with him and when I get to the house there are three more people there. They were all black [Daniels is African American]. They took advantage of me. It didn’t matter that I was like a two-year-old baby. They violated my whole body. I was sodomised, I was sick and he’s trying to stick his dick in my mouth. I’m just like, ‘Lord, hurry up. I promise I won’t do it again, just let them hurry up and get through so I can get the hell out of here’. I was treated even worse than an animal.”

During my visit to Auckland, New Zealand, I met Lisa, out on the streets looking for a punter. Lisa was sitting next to her Zimmer frame. It turned out she was in her early 50s and was disabled through a life in prostitution. I asked if her situation had improved since decriminalisation and she told me “no”, because in her experience the men who buy her feel entitled to do exactly what they want, in the way they would if purchasing a hamburger. “The only thing that would help me is a way out”, she said.

I use the examples above to illustrate what I have come to understand as fairly typical behaviour of sex buyers towards women in prostitution. I have heard countless stories - including from pro-prostitution lobbyists - of gang rape, beatings and stabbings, under legalisation / decriminalisation and every other legal system[17]. The men themselves admit to shocking attitudes towards the women they buy, and to having sex with distressed, terrified women. Some openly admit to being violent.

So why is there so much support for the punter from the liberal left? How is it that even the likes of Amnesty International appears to bend over backwards to protect his ‘human rights’ and to portray him as a man with needs he deserves to have met? Whenever I am discussing this issue with decent folk who should know better, they raise the issue of the disabled punter. “What about those men who can’t get a date the ‘regular way’?” they ask.

The Disabled Punter

As the various initiatives to curb demand for commercial sex have forced attention on the purchaser, the pro-sex-work lobby has acquired a new hero. The ‘disabled client’ (note the gender neutral description) is used to garner support, sympathy and to promote a view of the sex buyer as a nice, deserving individual. It is interesting to explore the type of disability these men are imagined to have by those whose sympathy is being sought. It is notable that the injured veteran and tragic young man figures keep recurring as examples – always heroic.

To hear the way many apologists for the sex trade describe disabled sex buyers, one could easily get the impression that selling sex to disabled people is an altruistic service, akin to meals on wheels. But the focus on this largely mythical buyer obscures both the majority of "undeserving" punters and the harms done to women.

In spring 2015, in a stiflingly hot TV studio in Manchester, England, I am sitting next to Laura Lee, who describes herself as a “part time call girl” and “sex workers’ rights activist”. We are waiting to pre-record an episode of O’Brien, a national UK TV programme in which we will debate the topic ‘Should we decriminalise prostitution?’

As the warm-up act tries to put life into the studio audience, I look around to see who, aside from Lee and a sex trade survivor I had met previously, is fitted with a microphone. There are a couple of heavily made-up women carrying whips and wearing fetish gear, and, in the front row, a middle-aged woman sitting next to a young, severely disabled man in a wheelchair. I could have written the script for what happens next.

Lee, who is so hostile to the sex buyer law she is mounting a legal challenge against the Nordic model introduced by the Northern Irish government in 2015, speaks about how prostitution is a choice for most of the women involved. I speak of the failure of legalised and fully decriminalised regimes, and why I support the sex buyer law. And the survivor highlights the harms caused to the women who are bought and sold.

The cameras then swishes around and focuses on the woman and the young man in the wheelchair. Her name is Veronica. She explains that John is her son, and that his back was broken in a car accident when he was five. As John approached puberty, Veronica began to worry about how he would meet his sexual needs.

“Should we have brothels on the high street?” asks host James O’Brien. “We should have brothels everywhere,” replies Veronica, before describing how she had trawled the internet looking for help with getting her son laid, speaking to “sex workers, escorts, prostitutes, anyone who knew about this”. Eventually, having been told about the massive sex trade in Las Vegas, Veronica took the aptly-named John to lose his virginity with several prostituted women. “He had a lovely time,” she says, with a cheeky twinkle in her eye. Laughter and clapping erupt from the audience. But there is more to come.

“Didn’t you buy him a brothel?” asks O’Brien. “So John, your mum bought you a brothel?”

“Yes,” John gloats, “and I lived in the basement for three years. I learned about all the different aspects of prostitution, and the dodgy side and the seedy side of it. But every man has got a different fantasy.”

“He wasn’t allowed to partake with any of the girls in our brothel,” interrupts Veronica, “because I didn’t want a situation where we could incur exploitation. I didn’t want him to be one of these guys – ‘oh, I’ve got a brothel so I’ve got rights to these women’.” The peels of laughter coming from the audience – including from a clapping, animated Lee – mask the sounds of disgust and protest coming from the sex trade survivor.

Sex tourist

This scene dramatised one of the most commonly used arguments against criminalising sex buyers. Pro-prostitution lobbyists claim that the Nordic model would, in effect, be criminalising ‘disabled people’. The argument holds that disabled people have a right to access to sex, with the implied premise that their disability somehow impairs their ability to form intimate relationships. This claim is one of the clearest examples of how the sex buyers’ so-called ‘human rights’ have been placed above those of the prostituted woman.

The ‘sex workers’ rights’ lobby argues that when disabled sex buyers are denied recourse to prostitution, they are being denied their dignity, liberty and the right to know physical pleasure and true love. There is even a not-for-profit organisation called Touching Base in Australia, which exists to “foster connections between people with disabilities and sex workers, with a focus on access, discrimination, human rights, and legal issues, and the attitudinal barriers that these two marginalised communities face”. Underneath the liberal language, this is pandering presented as a social service.

To make this argument more palatable, the ‘sex workers’ rights’ lobby claims that feminist abolitionists are denying the rights of sex workers to consent to prostitution and to practice their own agency.

The Disabled Saint

The myth of the sympathetic disabled punter has even been accepted by Amnesty International (AI). In its 2014 draft policy document (leaked to me by an AI insider, and which I subsequently published in a national newspaper) also takes the line that disabled men have a right to access sex via prostitution: “For some – in particular persons with mobility or sensory disabilities or those with psycho-social disabilities that hamper social interactions – sex workers are persons with whom they feel safe enough to have a physical relationship or to express their sexuality. Some develop a stronger sense of self in their relationships with sex workers, improving their life enjoyment and dignity.”

The suggestion that disabled people are considered so unattractive that they have to purchase sexual access to another human body is offensive enough in itself. Disability rights activists have long campaigned for better access to the venues where they might meet sexual partners, as well as a less prejudicial and conventional view of beauty. With the sanitisation of the sex trade by the ‘sex workers’ rights’ lobby and their academic enablers, terms such as ‘agency’ and ‘empowerment’ are increasingly applied to those selling sex as well as purchasing, particularly if the buyer is associated with a marginalised community.

Critics of the sex buyer law have found the argument about disabled men being denied sexual pleasure very useful in their campaign. However, it is less helpful to disabled people. Not only does it reinforce the problematic belief that anyone who does not fit the conventional standards of beauty and desirability is unable to access consensual sex and therefore needs to pay for it, it further suggests that disabled people’s carers are responsible for ensuring their clients sexual satisfaction. This is already the case in Denmark, where prostitution was legalised in 1999, and there is now an expectation that carers working with physically disabled couples should facilitate sex between them if asked – for example, the carer may be expected to insert the penis of one into an orifice of the other.

In the UK, a number of individuals and organisations campaigning for full decriminalisation of the sex trade use the example of disabled men and sexual access to garner support. In 2000, the pornographer Tuppy Owens set up the TLC Trust, a website for disabled men looking for prostitution services. The TLC website has this to say about the role of carers: “Health and social care professionals are often needed to support their disabled clients find a sexual service and prepare for each session. We hear dreadful stories of disabled clients being denied such support, and one sex worker reported that her client’s care team refused to wash him after a session! Please note: spunk is not disgusting or dangerous, in fact it is quite nutritious!”

Advice to disabled sex buyers on the site includes: “Question: My care staff refuse to wash me after seeing a sex worker. Answer: Threaten to report them unless they wash you respectfully.” On the fees charged by the escort services advertised on the TLC website, it has this to say: “Many disabled people say you cannot afford the fees that sex workers charge. Then we find out you have been on skiing holidays, own an expensive hi-fi, or smoke 20 fags a day. Where are your priorities? Remember, sex keeps you fit, mentally and physically.” With the mention of ‘skiing holidays’, it is clear that the escort services advertised by TLC are not only reaching out to men with significant mobility disabilities.

Its key message to disabled men about the sex trade is this: “Whatever you do, don’t feel bad about using sex workers – don’t fall for the fundamentalist feminist propaganda that all sex work is violence to women. For a start, many sex workers are men, and most sex workers chose their career because it suits them, and enjoy their work.”

Owens is also the chair of the Sexual Freedom Coalition (SFC). On its website, it states: “We actively challenge the Home Office, governments, religion, police and press for the sexual freedom of all consenting adults. It seemed important to focus on these people who are, in fact, doing great work in bringing happiness, inspiration and a sexual education to many people who need and enjoy them, including disabled people.”

The TLC Trust is demanding one wheelchair-accessible brothel in every city “to meet the demand”, and that hospice wards should have provision for visiting sex workers. TLC even uses the example of wounded servicemen to call for an ‘NHS’ approach to the sex industry. “It would be a sad injustice,” its website reads, “if service personnel such as soldiers badly wounded in Iraq and Afghanistan were banned from the help they receive from sex workers.”

Bärbel Ahlborn, coordinator at Kassandra, in Nuremberg, Germany, considers the provision of sexual services to disabled men partly as a health issue. “Many of the disabled and older people are not able to get into contact with sex workers,” she says. “If they are asking the nurses in the homes and tell them they want to find someone offering that [then] the nurses are feeling better with providing contact with a person who knows how to handle them.”

The idea that nurses are somehow responsible for assisting disabled patients to access prostitution is beyond comprehension. The majority of nurses and carers for the elderly and disabled are female. The vast majority of disabled people wishing to access prostitution services are male. Despite the pro-prostitution lobby, supported by a number of academics, insisting that prostitution is not about gender inequality, or violence against women and girls, the vast majority of prostitution transactions are male on female.

In 2005 I debated decriminalisation of the sex trade with a member of the Royal College of Nursing. As a result of lobbying by the English Collective of Prostitutes, the nurses’ union voted overwhelmingly to decriminalise all aspects of the sex industry at its annual conference in Harrogate in 1995, with the reasoning that this would make prostituted women more likely to come forward for healthcare.

My opponent was Jean, a middle-aged woman who considered nursing her vocation in life. I was surprised that Jean soon shifted her argument about women’s access to healthcare onto the poor disabled men who can’t get a date. Jean gave a heart-wrenching description of a returning war veteran named Jeff, whose legs were blown off and spine permanently damaged in a roadside blast. I expressed surprise that he had a fully functioning penis in spite of such injuries and was told: “Perhaps he just wants a human touch.”

This notion that ‘love’ as well as sex is for sale is one that is becoming increasingly popular among the postmodernist ‘queer’ identifying academics. In his review of the book Sex, Love and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships, Nick Mai, Professor of Sociology at Kingston University, argues that: “whereas ‘sex-for-cash’ can be seen as a practice close to prostitution, ‘sex-for-fun’, ‘sex-for-love’ and the ‘sweetheart relationship’ are discursively framed practices distinguishing different sexual, intimate and economic transactions through which professional girlfriends experiment with new individualised and hedonistic ways of ‘being themselves’ – sexually, socially and economically.”

But disabled people themselves don’t necessarily agree that they are in need of prostitution. I discovered the work of UK-based disabled feminist writer Philippa Willitts after reading her article ‘Nobody’s Entitled to Sex, Including Disabled People' on the blog Feminist Current. Over Skype, Willitts and I discuss the argument that criminalising the purchase of sex will lead to disabled men being unfairly punished.

She tells me that as both a feminist and a disabled person she was keen to ensure she made the point about the isolation and prejudice faced by many disabled people on the dating scene, while critiquing the rights of men to pay for sex. “I wanted to challenge this assumption that [disabled people] couldn’t have sex without paying for it, and that disabled men doing so was somehow inevitable,” she says. “I was sticking up for disabled people on the one hand, and sticking up for women on the other hand, so didn’t feel like I was compromising either of those identities.”

The rights of disabled men to buy sex clearly supersedes those of not only the prostituted women (or carers) expected to service him, but also that of disabled women campaigning to end the dual oppression of being disabled and female in a sexist, ableist society. For Willitts, challenging the misogynistic sex trade in no way contradicts her efforts in highlighting the social exclusion faced by many disabled people, which, in turn, makes it difficult to meet sexual partners.

She says: “A number of men I did not know, but who somehow came across the article, emailed me and said they were really glad to have someone represent the fact that they weren’t needy poor people with no friends or contacts, with no life.”

Why has the argument that disabled men routinely pay for sex become such a truism, I ask. “I wonder if it’s something about the fact that as disabled people we have to pay people to do things for us,” says Willitts. “If there’s something about the familiarity with needing assistance that removes a barrier?”

A number of academics in the UK and elsewhere have expressed concern about the sex buyer law impacting on the ‘human rights’ of disabled men. In a paper published in the journal Disability and Society, the Canadian authors argue that so-called ‘sex work’ is an important avenue through which disabled people can explore sexual fulfillment, and that the criminalisation of paying for sex would adversely affect disabled people and their right to access sexual pleasure. Again, the use of gender-neutral language here is interesting. They write: “Research has shown that the criminalisation of clients is a barrier to disabled peoples’ erotic lives because the sex industry can provide a valuable avenue for sexual fulfilment.”

Dr Belinda Brooks-Gordon, Reader in Psychology and Social Policy at LSE, UK, also supports the idea that prostitution services should be available on the NHS. In an interview with The Times, Brooks-Gordon said: “Given that sex therapy is available on the NHS for men with penile dysfunction, for example, we could make a good case for saying that it should be provided. At the very least the health service should explore all options available to help a patient in anguish. What about the young war veteran who has fought for his country and now has no legs, difficulty in finding a partner and can’t afford a prostitute?” At least Brooks-Gordon makes no pretence that there would be a demand for such ‘services’ from disabled women.

During a 2012 debate at Cambridge University entitled ’This House Would Decriminalise Prostitution’, Brooks-Gordon spoke in gushing terms of the fondness prostituted women have for their disabled ‘clients’. She said: “One sex worker said: ‘This week I saw a client with spinal bifida – I had to lift him from his wheelchair, position him, undress him, and then re dress him [and put him] back in the wheelchair. I was lucky he only weighed five stone. It’s one of the reasons why more than one lady on the premises can be a good idea.’ Another said: ‘I saw a Falklands hero who was injured [and had] no legs. [He] greeted me in his wheelchair, was an absolute gentleman. Sex [was] not possible for him [but he] derived pleasure from skin to skin [contact].’”

Gail (not her real name), a PhD candidate researching her thesis on an aspect of the sex trade, spoke to me about her views on the ‘rights’ of disabled men who pay for sex, a topic on which she had been published. Gail supports the theory that the disabled punter has been deliberately chosen as a sympathetic figure, and that there is a stifling conformity and fear of criticism within pro-prostitution academia.

Going by the arguments in her papers, there is no doubt that Gail is sympathetic to the rights of disabled men paying for sex. I ask her why she thinks those arguing most vociferously for full decriminalisation of the sex trade have recently used the example of disabled men’s rights to buy sex. “There’s a lot of violence from people who buy sex, and I agree that’s a massive problem,” Gail tells me, sitting outside a cafe in King’s Cross, London. “There’s not enough policing and protection, and working conditions are often really unsafe. [The argument that disabled men are also sex buyers] is making the point that not all people who buy sex necessarily are evil people. Disabled men are a small group of all people who buy sex.”

Don Kulick is a Swedish academic, currently Professor at Uppsala University, Sweden, and an influential voice against the Nordic model. In 2003 Kulick published a paper entitled ‘Sex in the New Europe: The Criminalisation of Clients and Swedish Fear of Penetration’ in which he described buying sex as “a temporary sexual relationship” and argued that the law criminalising the purchase of sex is a response to Sweden's entry into the EU. “For a variety of reasons, anxiety about Sweden's position in the EU is articulated through anxiety about prostitution.”

Kulick co-authored Loneliness and Its Opposite: Sex, Disability, and the Ethics of Engagement with Jens Rydström and has compared the Swedish law against sex buyers to previous criminalisation of same-sex encounters, and explains both as coming from a “fear of penetration”. Loneliness and Its Opposite is a comparative study of Denmark and Sweden and, according to the cover blurb, the differing ways in which disabled people’s sexuality and sexual desire is viewed and enabled. In fact, it is almost 300 pages of propaganda against the criminalisation of sex buyers, and in support of “sexual surrogacy”, “sexual assistance”, or straightforward prostitution services for disabled men. It is rarely mentioned that the vast majority of carers are female.

But this, in fact, is untrue. Where the two countries differ is not on respecting and upholding the human rights of disabled people, but on attitudes to and laws curtailing sex buyers. Sweden criminalises the purchase of sex, whereas Denmark does not.

In Loneliness and Its Opposite, the authors suggest that sexual pleasure should be facilitated by “people who work with and care for [disabled people]”, which means anyone who is tasked with general caring duties, such as cooking and shopping. Should a carer therefore not only provide personal care such as assisting the client with using the toilet or washing intimate parts of the body, but also, if we are sympathetic with the argument that disabled men have a right to sexual release, facilitate orgasm?

Kulick and Rydström’s data gathering is based on classic anthropological fieldwork, or ‘participant observation’. Rydström spent one month living in three separate group homes for disabled people in Denmark. In Sweden no such fieldwork took place. Why? According to the authors, there was no point: “Perhaps there is a group home, somewhere in Sweden, that has affirmative practices that facilitate the sexual lives of people with disabilities. But if such a place exists, it is a well guarded secret, unknown to or undisclosed by any of the professionals who work with and write about sex and disability and unknown to any of the Swedes with disabilities to whom we spoke.”

This leap of logic is staggering. It is clear the authors are only looking for very specific “affirmative practices” regarding the facilitation of sexual pleasure, such as assistance to procure prostitution services. It might have been useful to spend time in the group homes in Sweden to ask the caring staff whether they would make a distinction between assisting someone to urinate or defecate, and assisting them to ejaculate.

Chapter 1 of their book opens with an example from a ‘sex educator’ named Axel Branting. Some years ago, a paralysed woman in her 30s came to Branting for advice. The woman told Branting that she had a problem: every time her male carers lifted her out of her wheelchair, she had an orgasm. “What’s the problem?” asked Branting. Well, said the woman, the male carers had clearly noticed her sexual arousal and, whenever possible, handed the task of lifting her to the female carers. Feeling depressed and humiliated, the woman had no idea how to raise the issue with the carers.

“And so he offered her the only piece of counsel he could think of. Turning centuries of advice prescribed to sexually unfulfilled women on its head, Branting told her that the next time one of the male assistants lifted her, ‘Close your eyes and pretend like you’re not having an orgasm.’”

Branting had assumed the male carers were “afraid” that they might be leaving themselves “open to accusations of abuse”. The idea that the carers did not want to be part of a one-sided sexual tryst with a client did not occur to him. The notion that this woman was entitled to “sexual fulfillment” from her carers is staggering. Clearly painting her as some type of victim, the conclusion of Kulick and Rydström is that, despite the men being clearly unwilling and therefore most definitely not consenting, the disabled woman should take whatever sexual pleasure she could find, while hiding the evidence.

The example of a disabled woman becoming aroused and desiring ‘sexual assistance’ from male carers belies the far more common scenario, which is of course that of disabled men and female carers. The authors, whether intentionally or otherwise, have used a sanitised version to make this point. Had they provided a scenario of a male carer being assisted by female carers, they would have had to deal with the messy reality of sexual harassment and spurting ejaculate.

The authors also cite the academic Dr Michelle McCarthy, author of Sexuality and Women with Learning Disabilities. McCarthy’s study is seen as somewhat irrelevant in terms of the arguments made in Loneliness and Its Opposite.

“Sexuality and Women with Learning Disabilities is concerned primarily with sexual abuse,” write Kulick and Rydström. “This focus seems to be partly because of McCarthy’s particular interests and the manner in which she recruited her respondents [all of the women she interviewed had been referred to her by a group that provided sex education for adults with intellectual impairments] and partly because McCarthy says that the women she interviewed did not have very positive views of sexuality. Most of them had been victims of sexual abuse.”

I asked McCarthy her views on why her study had been deemed irrelevant by Kulick and Rydström: “It’s true to say that all of the people came through a sex education project but the majority of women who were referred for sex education had been sexually abused. Isn’t that interesting?” she says. “It could have been a sample of women who just needed sex education or advice on contraception or how to seek more sexual pleasure or whatever. As it turned out the majority had been sexually abused. I didn’t seek them out, that’s how they came.”

McCarthy is clear that when sex trade apologists speak of providing ‘sexual services’ for disabled people, it is actually about male privilege: “I have never heard of male sexual surrogates being provided to women with learning disabilities. Most of the men who work in the sex trade service other men. Where are they going to find legions of men to work with women with learning disabilities?”

One of the ‘tips for sex workers’ from the Sexual Freedom Coalition shows very clearly the way that many simply assume that even the most severely disabled men will automatically want and need sex: “Where consent cannot be expressed because of severe disability, assumptions should not be made that sexual pleasure is not required.” This is genuinely a horrifying comment that raises the prospect of non-communicative disabled people being subjected to unwanted sexual contact.

Wilitts is appalled at the way that able-bodied sex trade supporters are using the example of disabled men in order to discredit the sex buyer laws. But she is also concerned that a number of disabled men have internalised the ‘human rights’ rhetoric about sex. “Nobody ‘needs’ sex,” says Willitts. “And rather than disabled men campaigning for prostituted women to service them, they should be focusing their attention on making spaces – such as clubs where we may meet sexual partners – more accessible. I think the disabled community needs to look at whether it’s ignoring women’s rights.”

‘Performance boxes’ in the prostitution zone, Zurich, Switzerland

There are a number of other rationalisations put forward by those defending the right of men to pay for sex. One is that men ‘need’ more sex than do women, and therefore have no ‘choice’ but to access via prostitution. This is akin to the regressive, outdated view, circa 1950, that men who do not get enough sex are compelled to rape. As one sex buyer said to me in the 2009 London study: “Prostitution is a last resort to unfulfilled sexual desires. Rape would be less safe, or if you’re forced to hurt someone or if you’re so frustrated you jack off all day.”

Dr Catherine Hakim is a sociologist currently based at the free market research group, Institute for the Study of Civil Society, London, UK. Hakim believes that prostitution is inevitable because of what she has termed the “male sex deficit”. Hakim’s report ‘Supply and Desire: Sexuality and the Sex Industry in the 21st Century’ was handily published the day before AI made public its decision to support a policy of blanket decriminalisation of the sex trade in August 2015. Hakim, who has relied on secondary research and does not appear to have actually interviewed any women in the sex trade, argues that men want more sex than women and therefore it is inevitable that men will pay for sex.

I have debated with Hakim on the topic of blanket decriminalisation. At one event at the University of York, in 2015, myself and Broadfoot debated with Lee and Hakim. The motion was ‘This house believes decriminalising prostitution would be a disaster’. During the debate, which everyone except Hakim agreed could be recorded, Hakim put forward her theory that prostitution will always exist because women want sex with their male partners significantly less than men do with their female partners. I cannot quote her directly here as I was unable to take notes, but this quote from Hakim’s paper below should give a fair impression of her thesis:

“Our gender-neutral theory of prostitution is that the ubiquity of sex workers, both male and female, even in countries where commercial sex is banned, and the high earnings of sex workers, both male and female, are explained first and foremost by the male sexual deficit which produces high male demand and relatively low female supply of sexual entertainments, both professional and amateur, within and outside marriage. Kontula (2009) concluded that overall, male sexual desire is manifested at least twice as often as female desire, and men would like to have sex twice as often as women. This is a huge gap between supply and demand, and it is exacerbated by the fact that men generally prefer to have sex with young and attractive women (or men).”

I asked Hakim that if men had to pay women who did not want sex in order to have sex with them, was that not rape? Hakim looked blank and Lee declined to support her thesis. By arguing that women in relationships with men do not desire sex to the same degree as their male counterparts, Hakim is framing the sex of prostitution these men seek as a girlfriend substitute.

The Protector of the Punter

A number of women who define as feminist are against the law criminalising demand, many of whom are part of the ‘queer’ community. The ‘queer’ approach is examined in detail in chapter 10, but I mention it here because a number of those academics and activists that claim to speak on behalf of disabled punters use this argument. For example, Siouxsie Q, a pornographic actor and ‘sex workers’ rights’ activist based in San Francisco, US. I met Q at the Porn Awards in Los Angeles in 2015 and we later connected by Skype.

I asked Q her view on the Nordic model. “I don’t believe that clients are the issue,” says Q. “It is founded completely in moral prejudice and a panic about the idiom of selling sex in any capacity. We do a job and we have clients. Do people who are hairdressers have slimy annoying clients who don’t tip sometimes? Absolutely. Does that happen in the sex industry? Sure. But does criminalising the client help? Absolutely not. That puts a contentious relationship between client and sex worker that compromises their safety, their viability, their money.”

A number of self-identified feminists profess support for the sex buyer, including a number of female academics as we will see in chapter 9. Why is this? In her brilliant article, ‘The modern John got himself a queer nanny' posted on the blog Feminist Current, Swedish journalist and feminist abolitionist Kajsa Ekis Ekman explains the phenomenon as such:

“The tacit agreement between the John and the pro-prostitution female academic is that she will do anything to defend his acts, while ensuring that he stays in the shadows. She will speak incessantly about prostitution, but never mention him. Her task is to make sure prostitution seems like an all-female affair. The queer academic will use the prostituted woman as a shield, blocking the John from the limelight. She will use the prostituted woman any way she can - analysing her, re- and deconstructing her, holding her up as a role model, and using her as a microphone (ie a career booster), thereby positioning her as ‘good’ vs the ‘evil’ feminist.”

The Keith Vaz Scandal

In the UK, a scandal of epic proportion hit the Home Affairs Select Committee, which overseas the justice system, and which is with recommending law and policy on prostitution. In the Autumn of 2016, the Chair of the Committee, Keith Vaz MP, was secretly filmed by a young Romanian man who Vaz had paid for sex. During the exchange, Vaz was heard arranging for another prostituted young man to be brought to him, and pondering on who was going to “break him in” and “fuck him first”.

Soon after the Vaz scandal erupted, disgraced member of parliament Simon Danczuk tweeted: “I'm right in saying Keith Vaz hasn't done anything illegal, aren't I?” In 2015, Danczuk himself had exchanged ‘sexually explicit’ text messages with a 17-year-old female job applicant. Police investigated the matter (under the Sexual Offences Act 2003, the age of consent is 18 in circumstances where the accused is in a position of trust) and decided that no offence had been committed. There was strong criticism of Danczuk by many of his constituents in Rochdale, a town in the north of England, because he was best known for his campaigning work on historical child sex abuse.

When the story broke about Vaz, abolitionists called for it to be known that as Vaz is a sex buyer, we most certainly should be questioning the validity of the enquiry. An interim report that more-or-less recommends full decriminalisation of the sex trade should be declared null and void, bearing in mind that its chair has such a vested interest in preventing the criminalisation of punters.

The Research

The research, headed by Melissa Farley in six countries and based on interviews with over 700 sex buyers showed very clearly that many of the men are ambiguous about paying for sex. The quotes below highlight some of the self-disgust and shame that the men grapple with:

• “I wouldn’t encourage prostitution – it’s someone’s mother or daughter. It’s an empty experience. It sounds enjoyable at the beginning but it’s just horrible, degrading.”

• “I don’t get pleasure from other people’s suffering. I struggle with it but I can’t deny my own pleasures. In Cambodia I knocked back a lot of children, it makes it hard to sleep at night. But I don’t see the point in making a moral stance.”

• “Most of the men who go see it as a business transaction and don’t see the girl as a woman. This could impact on how a man sees women in general.”

The same research also shows that many of these punters could easily be deterred. As one punter told me, when I interviewed him for the London study: “Deterrents would only work if enforced. Any negative would make you reconsider. The law's not enforced now, but if any negative thing happened as a consequence it would deter me.”

When it comes to prostitution and the sex industry in general, the law is often an ass. Unless the human rights approach of criminalising the punters is adopted, most countries will have laws under which the pimps, punters and brothel owners walk free while those desperate enough to be selling sex are punished. But the so-called ‘human rights’ approach of today, as we will see in this next chapter, is to support the notion that to name prostitution as abuse, contravenes the human rights of the women that wish to sell sex.

Thank you Julie Bindel for this extract, and for your incredible, tireless work. You are magnificent.

Prostitution and surrogacy are (sometimes) consensual. The idea of consent relates to the "human rights of the women that wish to sell sex."

Consent is such a misleading and opaque word.

Women consent to things all the time, including sex, with no desire or enthusiasm.

The world of Psychotherapy/Psychology never looks at the psychological consequences of consensual but unwanted sex. The wider world also never looks at the physical consequences of prostitution (or surrogacy).