A FREEDOM WORTH HAVING:

THE PROPOSED REPEAL OF THE HIGHER EDUCATION (FREEDOM OF SPEECH) ACT 2023, a guest post by Akua Reindorf KC

An edited version of this article was first published in the New Statesman on 2 August 2024

Akua Reindorf

It is seven years since veteran feminist campaigner Linda Bellos was disinvited from a speaking engagement at Peterhouse College, Cambridge on the basis that her views on transgender rights were a threat to the welfare of students. Two years later, journalist Julie Bindel was physically assaulted by a protester as she left a talk she had given about male violence against women and girls at Edinburgh University.

There has followed an escalation in the targeting of feminists in academia. In 2020, Professor Selina Todd revealed that her employer, Oxford University, was providing security guards to accompany her to lectures because of threats to her safety. In 2021, colleagues of Professor Jo Phoenix at the Open University published an open letter signed by 368 academics demanding that the institution withdraw support for the research network she had founded. She was compared to “a racist uncle at the Christmas dinner table” by her Head of Department. Meanwhile, Professor Kathleen Stock was enduring a relentless campaign of harassment and vilification in her workplace, Sussex University, which culminated in her resignation in the face of campus protests by black-clad men in balaclavas setting off flares and the University and College Union publicly supporting her aggressors.

These are women who have suffered persecution because they attempted to engage in academic debate about the conflict between women’s rights and the claims made by transgender rights activism, expressing views which are well within the realm of lawful and reasonable opinion. They are just some of the high profile campaigners and academics at the peak of their careers whose stories have hit the news. For every one of them, there are others without public profiles, secure tenure or seniority who keep their heads down, and countless more who keep their eyes shut.

It is a trite phrase often heard that academic freedom is the lifeblood of universities. You do not have to be a gender critical feminist to recognise that the experiences of the women named above call that into question. Academic freedom is the principle that academics should be able to challenge received wisdom, established doctrine and dogma through critical thinking, open enquiry and dialogue, without risking their jobs or privileges. It is a fairly niche concept, but one which has hitherto been regarded within higher education as an article of faith because of its crucial role in producing rigorous scholarship.

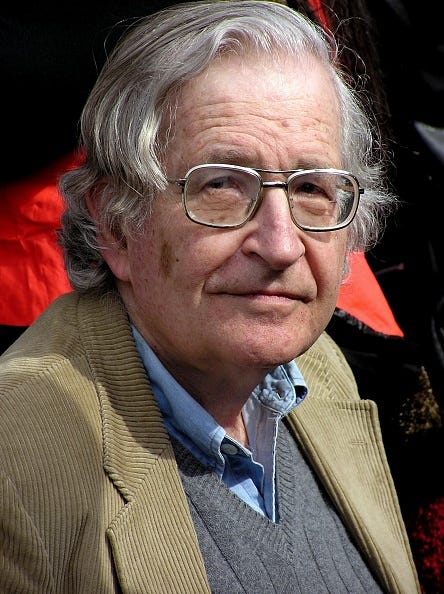

The idea began when academics started demanding freedom from interference by vested interests – first the Church and then the state – in the early part of the last century. Fresh impetus came from the civil rights movement and radical student activism of the 1960s, from which emerged the Council for Academic Freedom and Democracy, founded at the LSE in 1970 by Ralph Miliband and championed by Noam Chomsky. This left wing pedigree makes perfect sense. Academic freedom is a close cousin of freedom of expression and freedom of conscience; human rights principles which were the building blocks of twentieth century left wing thought.

Noam Chomsky

Today, it is neither the Church nor the state that imperils the intellectual and moral autonomy of academics. Nor is it the left that champions it. The threat now comes from inside the academy, and specifically from many of those within it who identify as left wing. Often it is a family affair; those who are targeted by the censorious are usually women and men with long-standing left wing credentials.

But it is difficult for university leaders to challenge this depressing status quo. They are buffeted by the demands of marketisation, highly questionable advice on their equality, diversity and inclusion policies from partisan lobby groups, the often eccentric demands of accreditation schemes and a workforce which suffers from unprecedented levels of precarity in employment and so tends towards conformism rather than courage.

That is part of the background against which the last government passed the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, now put on hold and apparently headed for repeal before most of its provisions have even come into force. The central purpose of the new Act is to place duties on English and Welsh higher education providers both to “take reasonably practicable steps to secure” and to “promote the importance of” freedom of speech within the law and academic freedom. It also requires students’ unions to take reasonably practicable steps to secure freedom of speech within the law.

The Act contains almost no new law. Universities are already under a surfeit of statutory and regulatory obligation in this area: the duty to secure freedom of speech in section 43 of the Education Act (No. 2) 1986; the registration conditions imposed on universities by the Office for Students; the requirements of Articles 9 and 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which deal with freedom of thought, conscience and religion and freedom of expression; section 10 of the Equality Act 2010, which protects individuals from discrimination because of philosophical belief; obligations placed on universities by the Charities Act 2011 and the requirements of the Charity Commission. Students’ unions are subject to charity law and regulated by the Charities Commission, and are subject to the Equality Act 2010 in respect of many of their functions.

But this is a tortuously complex legal landscape, and it yields surprisingly little by way of realistically enforceable rights for individuals whose academic freedom or freedom of speech has been infringed. Currently, the only viable route to a remedy is through a claim of philosophical belief discrimination under the Equality Act 2010. But these are enormously expensive and time consuming cases for both parties. There is very little chance that even a successful litigant will recover their costs, which will often vastly outstrip any possible compensation. Furthermore, the Equality Act 2010 does not give any rights to visiting speakers like Linda Bellos and Julie Bindel and it has only patchy coverage for claims against students’ unions.

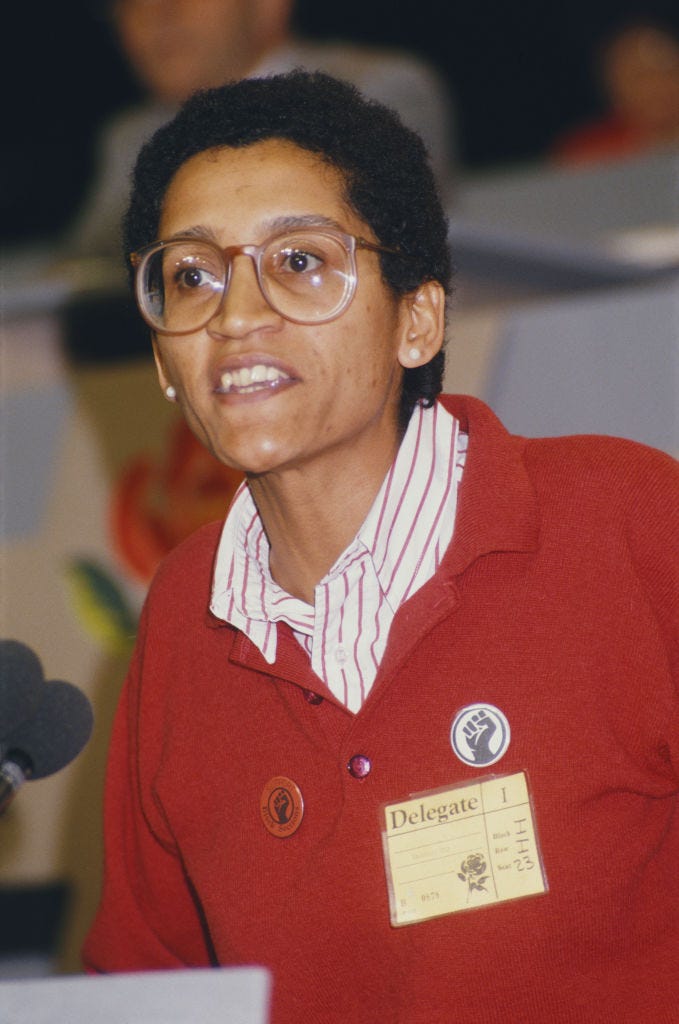

Linda Bellos, 1987

What the new legislation does is to give the existing law teeth. It is by no means perfect, but it has the substantial benefit of bundling together the law in this area into a package that contains an accessible enforcement mechanism: a complaints scheme to be operated by the Office for Students. Cases may be taken to court, but only after the complaints process has been exhausted.

The displeasure of many university leaders at the prospect that academics will be able to enforce their rights has somewhat surprisingly been heeded by the Labour government, which appears to be taking the side of institutions against individuals deprived of a just remedy for unlawful conduct. If we have law, it should surely be able to bite. And this is not just any unlawful conduct; it is conduct which breaches the right to freedom of expression, the cornerstone of all human rights.

In any case, the protests of the university administrators are surely misplaced. The OfS complaints process will be free and should be relatively speedy, and complainants may not take a case to court until the complaints process has run its course. The filter of an efficient and informal scheme of this sort seems bound to represent better value than the financial drain of interminable employment tribunal cases like that brought by Professor Phoenix against the Open University. If a case does end up in court, it will be in a civil court in which legal costs can usually be recovered by the winner.

The government has also expressed concern that the new Act will negatively impact the welfare of students from minority communities, a view shared by the National Union of Students and other stakeholders. From a legal point of view this is a puzzling objection. It pitches the right to freedom of speech against the rights of minorities not to be subjected to hate speech as though there is not already a mature and well developed framework of legal principle which holds these rights in careful balance, to which the new Act would be subject.

In particular, the idea appears to have taken hold that the Act would give the green light to Holocaust deniers to spread their dangerous rhetoric to impressionable young minds. Certainly it would be a worry if that were the case. But it is vital to be clear about this: Holocaust denial is not and will never be protected by any free speech laws. The European Court of Human Rights has specifically ruled that, even if it is dressed up as impartial historical research, it falls entirely outside the scope of the Human Rights Convention because of the operation of Article 17. The same is true of any other “hate speech” of a similar gravity, such as the promotion of totalitarian ideologies. The law would never force a university to allow a swastika to be displayed on its premises.

Nor will the new Act open the floodgates to other unlawful speech. This includes discriminatory harassment which breaches the Equality Act 2010 or stalking behaviour which contravenes the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. It also includes criminal speech such as incitement to hatred on grounds of religion, sexual orientation or other protected characteristics under the Public Order Act 1986, intentionally encouraging or assisting another person in committing an offence contrary to the Serious Crime Act 2007, the sending of malicious communications in breach of Malicious Communications Act 1988 and criminal harassment within the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. And, sitting behind all of these legal restrictions, Article 10(2) of the Human Rights Convention allows legitimate and proportionate interference even with lawful speech.

But beyond that, to paraphrase Lord Justice Sedley, we must give our great thinkers and those they train the freedom to stray into the controversial, the offensive, the irritating, the contentious, the heretical, the unwelcome and the provocative. The freedom to say only uncontroversial things is not a freedom worth having, and challenging consensus is what universities are for. We must hope that repeal is not a done deal, and try to persuade the government to take a level headed approach to it. As the examples at the top of this article show, this is not about petty “culture wars”; it's about people’s lives, livelihoods and fundamental human rights.

© Akua Reindorf KC

15 August 2024

A useful summary. Thank you.

I need some help remembering how the New atheist movement got so sexist and helped spawned the red pill movement? One if you lovely ladies help me identify the inflection points?

I think it's important to point out how even the diversity papers by Helen, Pete and James false-teamed liberal and radical feminism.

When future historians look back on this age, they will see the uniformed vilification of feminist thought as the destructive conceptual line that runs through current woke and conservative anti women movements.